Siobhan Wescott keeps a small framed photo in her office that reminds her of home — and of just how far she’s come. It’s a picture of a wide dirt road in a forest near the tiny cabin outside Fairbanks, AK, where she grew up. Along the horizon, the road meets a billow of smokelike clouds, then fades to a white nothingness.

As kids, Siobhan and her brother, Liam, would sometimes walk that road to catch a ride to school, clambering over snowdrifts to get there.

Siobhan, now 56, is an Alaska Native of the Athabascan tribe and one of the few Native people in the U.S. to hold an endowed professorship. (She holds both an M.D. and an M.P.H., serving as the director of American Indian Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.) “The Athabascans are a group that is inherently nomadic,” says Siobhan, which might explain the many addresses she’s had over the years. “But even nomads find a way to have a home base. Alaska always seemed like home.”

Today, Fairbanks is the second largest city by population in Alaska, a hub for regional transportation, military operations and a thriving tourism industry. But Siobhan’s ancestors survived their harsh homeland not by relishing their surroundings but by moving constantly, following the migration of animals. “They lived in small bands with simple camps that could be broken down and carried to the next hunting site,” she says.

Similarly, Siobhan’s path to health care, policy and teaching wasn’t a straight line. She and her mother, Betty Parent, are living proof that you don’t have to remain static to stay in touch with your roots. “I made my way to medicine because of the impact that illness and bad policy had on my family,” she says, her dentalium shell hair ties — a gift from her mother — highlighting the silvery threads in her hair. “But to tell my story, I need to start with my mother’s.”

“No Dogs, No Natives”: A Brutal History,

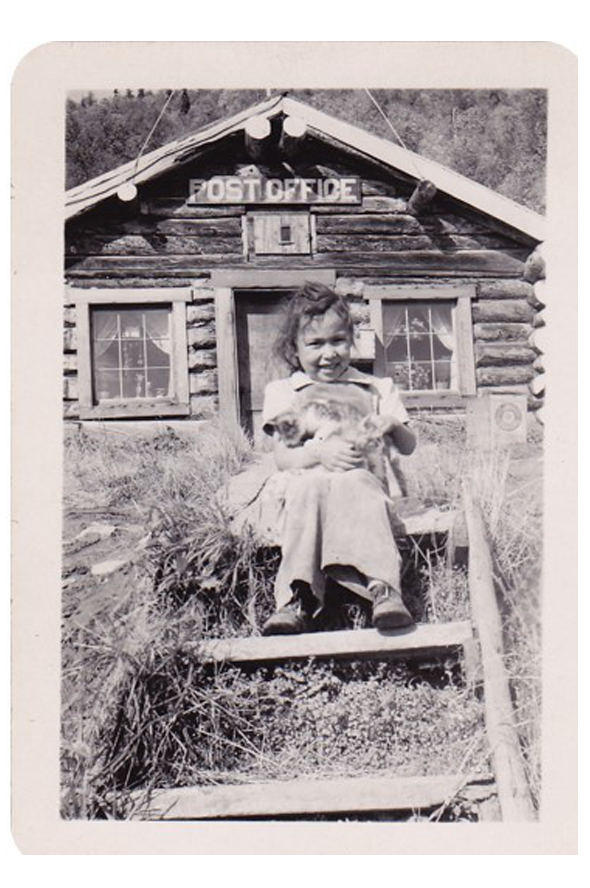

Siobhan’s mother, Betty, doesn’t try to downplay the struggle that lives behind her own incandescent smile. “I had a very hard early life. For my generation in the territory in Alaska…it was very rough,” Betty says. She was born in 1941 in Bethel, AK, and lived in Crooked Creek, a remote village with a population of 55.

As a small child, she lost her entire family, several to tuberculosis, a disease brought to the region by explorers and missionaries. Betty had already suffered family tragedy when her father drowned in an accident when she was 3; later, her mother contracted TB. Betty recalls that at some point her mother went to an Alaska Native hospital to have a baby, whom she had to leave at the hospital. That child was adopted out to a white family, which was a common practice at the time. Alaska Native children who became “orphaned” were adopted out to non-Native families even when they had Native relatives who could have cared for them.

This appalling practice occurred nationwide, with 35% or more of Native children being removed from their families and put in non-Native foster and adoptive homes. This changed only in 1978, with the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act, which the Supreme Court just voted to uphold this past June. Betty’s younger sister, Irene, also contracted TB and eventually died in a hospital in Washington.

Beginning at age 4, Betty lived with an aunt. “I had to be hidden,” she says. Otherwise, her aunt feared, the government would take Betty (“White families would ‘shop’ for Native babies to adopt at the public health hospital,” Betty says) or her mother might come back, disrupting the stable home the aunt was providing for her.

Despite her hardships, Betty proved to be an extremely bright child and excelled in school. By her sophomore year, she was attending a Catholic boarding school in Seattle. She went on to get a degree from the University of Alaska, a master’s degree from Harvard University and a Ph.D. from Stanford University, the first Alaska Native woman to do so. She later became chair of the American Indian Studies department at San Francisco State, hosted a PBS show and was inducted into the Alaska Women’s Hall of Fame.

Bad Policy = Bad Outcomes

Siobhan’s own nomadic journey also started when she was 4. That was when Betty moved the family to Cambridge, MA, after she and Siobhan’s father separated. Unfortunately, Siobhan was bullied by some of the other kids at Harvard’s preschool when she told them she was Indian. “They thought it was a game, cowboys and Indians,” she says.

It was traumatic, but it steeled Siobhan against other difficult experiences and pushed her toward achievement. She got a degree in government from Dartmouth College, a master’s in public health from the University of California and an M.D. from Harvard Medical School, where she was the oldest graduate in her class at the age of 40. Each additional degree gave her one more tool to effect change in her community, her ultimate goal.

“I wanted to change things so that no one would have to go through what my family went through in the 1940s,” Siobhan says. “If you don’t have good medical treatment and you also have policies that tear families apart, you get bad outcomes for a population.”

Improving health care access and recruiting more Native physicians are two of Siobhan’s focuses today, especially given that Native doctors still make up less than 1% of U.S. physicians. Her position as the Dr. Susan and Susette La Flesche Professor of American Indian Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center is named for two sisters from the Omaha tribe, Susan and Susette La Flesche. Susan La Flesche was the first Native American physician, graduating from medical school in 1889 and running her own practice in Nebraska.

“Even the Simplest Thing Isn’t Simple”

As part of her role at UNMC, Siobhan leads a project called Nebraska-Health, Education, Advocacy and Leadership Across Indigenous and Native Generations (NE-HEALING). The project involves understanding and serving the Native community in Nebraska and across the country. One of the first steps in healing is understanding the role identity and labels have played in Native communities. “Racial identity is complicated. Even the simplest thing isn’t simple,” Siobhan says. Take her own background: Her great-grandfather was an Indigenous Norwegian Sami, or Laplander, and his family lived off the land. In the late 800s, at age 14, he ran away from home, stowing away on a ship carrying reindeer from Norway to Alaska. “His race was ‘white,’ but that didn’t capture the story of his heritage,” Siobhan says. In addition to being an Alaska Native, she is also Norwegian, Irish, English, Swiss and French.

That rich multiethnic, multiracial identity is more common than not. The number of Americans who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native nearly doubled between 2010 and 2020, jumping from 5.2 million in 2010 to 9.7 million in 2020. This was in part due to better-designed race and ethnicity census questions and improved community outreach and engagement regarding the importance of census participation, says Donald Warne, M.D., M.P.H., a member of the Oglala Lakota tribe from Pine Ridge, SD, and codirector of the Center for Indigenous Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

What hasn’t improved is the terminology used for Indigenous people in the U.S., and this is another issue Siobhan is trying to tackle. “I put together an Indigenous-led research team to study terms people have used, and we discovered that the vast majority of the terms for Native people have been imposed by others, not chosen by the communities themselves,” she says.

Such imposition on Native communities is at the root of much bad policy, because when others define who you are, they also tend to decide what’s best for you, explains Dr. Warne. For example, Navajo Nation is their legal name, but “Navajo” is a Spanish word imposed on the group (they call themselves Diné), and “American Indian” — the federal government’s racial designation for Native people — is based on Christopher Columbus’s more than 500-year-old mistaken belief that he was in India when he landed in the Americas.

Siobhan would like to see leaders of Native communities guide the conversation about updating and improving the terms governments and institutions use. The

general public may understand the term “American Indian,” but it is a misnomer.

Restoring Health — and Hope

Healing” is in the name of Siobhan’s UNMC project and also at its heart. The physical aspect of healing is part of her job as a physician, but thanks to her public health background, Siobhan knows that recovery also depends in large part on building trust. That’s one thing she’s trying to do among the Native communities in Nebraska. Inspired by the AIDS quilt, Siobhan is working to create a quilt memorializing Indigenous lives lost to COVID-19. “As I’m working with the Nebraska tribes to get the COVID quilt underway, I’m also asking them, ‘What are your urgent health needs?’ ” Siobhan says. That’s how healing starts: through asking questions, listening and practicing “collective decision-making,” which involves making sure all groups have a seat at the table.

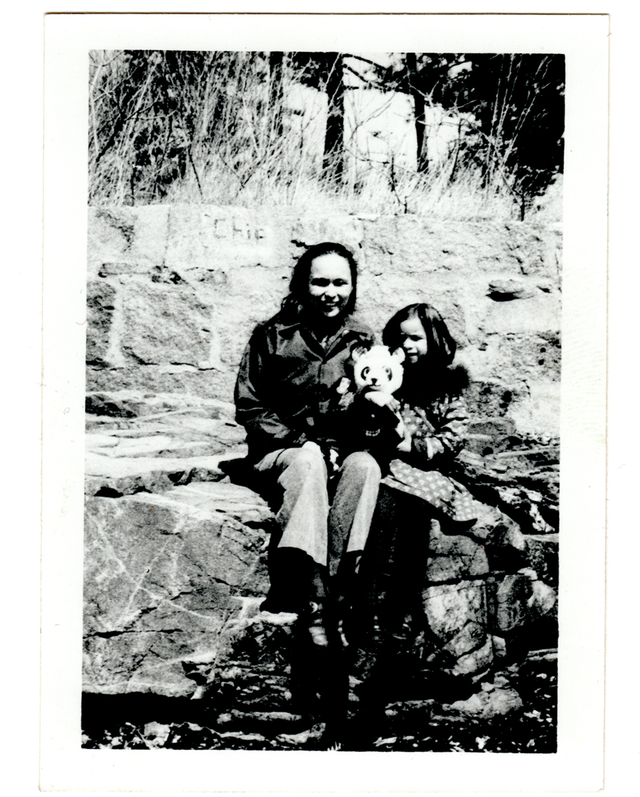

Betty is unbelievably proud of her daughter’s work and sees Siobhan’s story as an updated version of her own. “Hers is a different generation because her parents were faculty members, whereas mine didn’t finish high school,” Betty says. Siobhan also has the benefit of modern, practical tools to help her move through inherited generational trauma. “Going through medical and public health training helped me frame feelings brought about by my trauma and keep it from controlling my life,” she says.

When she gets stressed, Siobhan turns to an ancient art, beadwork. “Beads are the pixels of Natives,” she says. It soothes her mind. Perhaps her nomadic heritage is one reason Siobhan has never worried about getting fully lost or stuck. “That nomadic pull still calls to me,” she says. “It’s a fundamental part of me, a gift from my ancestors.” A gift that, as they say, keeps on giving, generation after generation.