The Licensed Behavioral Health Workforce in Nebraska: 2010 to 2024

Purpose

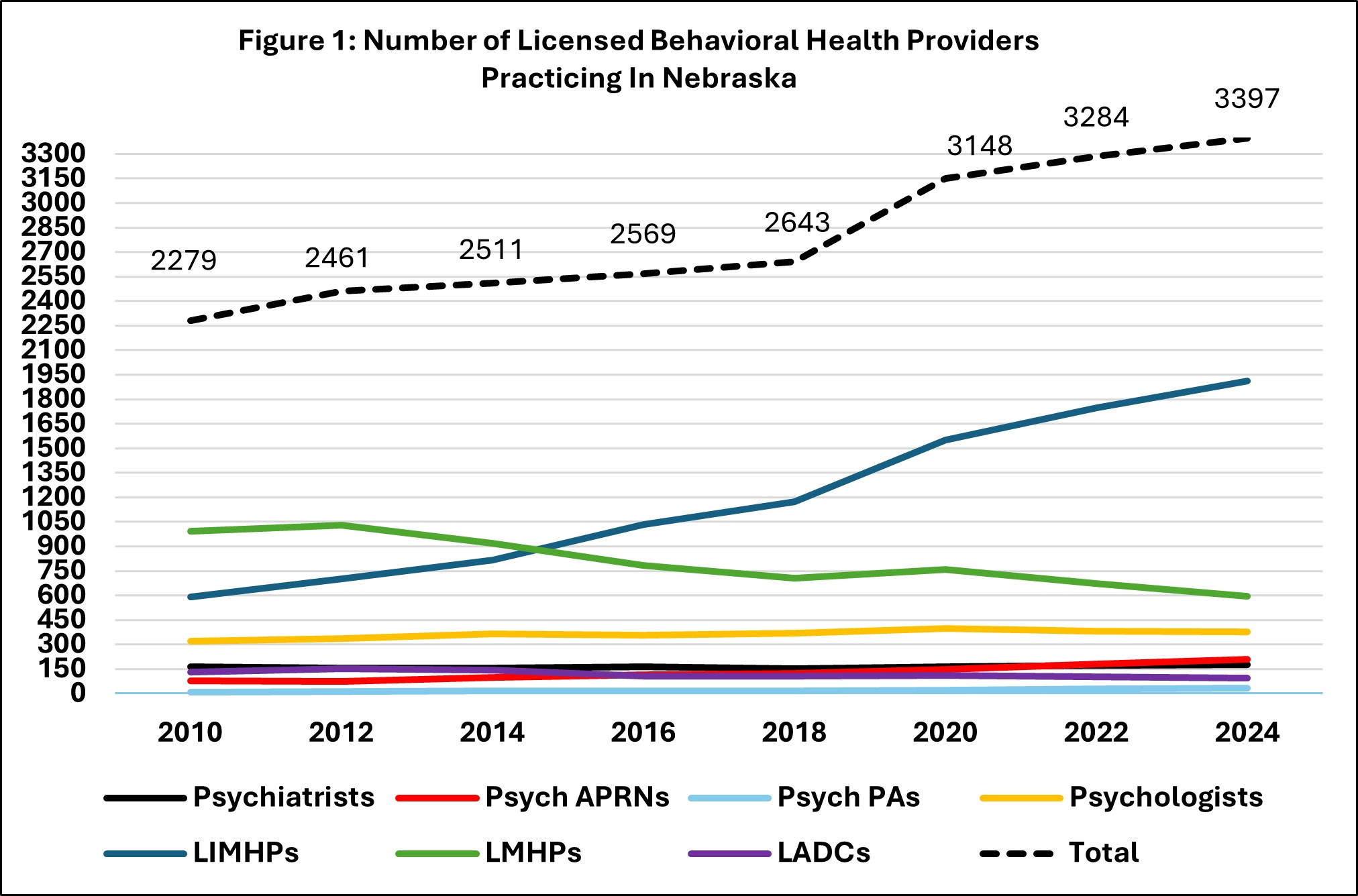

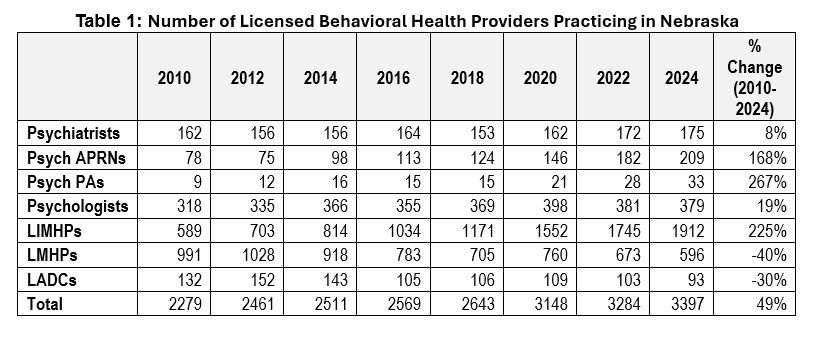

Since 2010, BHECN has tracked behavioral health workforce trends for Psychiatrists, Psychiatric Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), Psychiatric Physician Assistants (PAs), Psychologists, Licensed Independent Mental Health Practitioners (LIMHPs), Licensed Mental Health Practitioners (LMHPs) and Licensed Alcohol and Drug Counselors (LADCs).[1], [2],[3] This snapshot presents data for 2010-2024.

Key Findings

-

The Nebraska behavioral health workforce grew steadily from 2010 to 2024, with the number of providers increasing by 49%.

-

Some provider types experienced major growth, including Psychiatric PAs (267%), LIMHPs (225%), and Psychiatric APRNs (168%).

-

There has been progress in reducing provider shortages in rural areas, including a 24% increase in the number of rural behavioral health providers, and increases in 40 rural counties.

-

Despite these positive trends, high demand for services combined with behavioral health provider shortages in some rural and under-resourced communities means it is still difficult for many residents to obtain behavioral health care.

Behavioral Health Workforce Trends: 2010-2024

Figure 1 and Table 1 summarize information about the number of licensed behavioral health providers in Nebraska from 2010 to 2024. There was a 49% increase in providers (from 2,279 to 3,397), with increases in 50 Nebraska counties (40 rural counties and 10 urban counties).

Psychiatric PAs, LIMHPs, and Psychiatric APRNs experienced the greatest growth. The number of LMHPs decreased as the number of LIMHPs increased, suggesting a conversion of LMHP to LIMHP licenses. Although hierarchical counts of LADCs show a 30% decrease from 2010 to 2024 (from 132 to 103), non-hierarchical counts[4] show a 53% increase (from 362 to 553). This discrepancy suggests increases in dual licensure over time.

Rural Workforce Trends

Providers in rural counties increased 24% since 2010 (from 584 to 727), with increases in 40 rural counties. Graduates of rural training programs and those with rural hometowns are most likely to practice in rural Nebraska counties.[5]

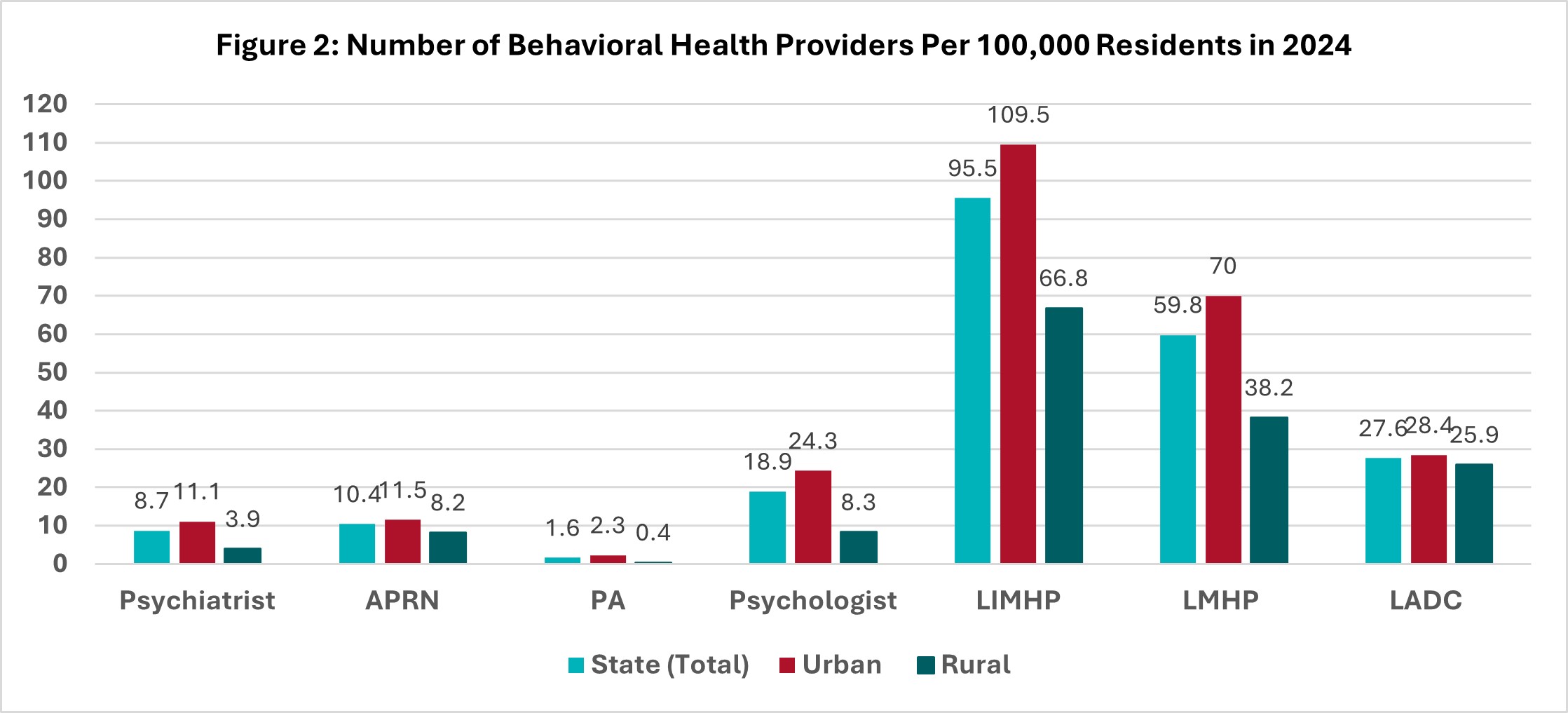

The professions that have seen the greatest percentage increase in rural areas since 2010 are LIMHPs (214%), APRNs (129%), PAs (50%), and Psychiatrists (24%). While urban growth has outpaced rural growth overall, Psychiatrists and LADCs have seen proportionally more growth in rural areas compared to urban areas in the last 5 years. Currently, APRNs and LADCs come the closest to parity between rural vs. urban availability per 100,000 population.

Still, rural counties continue to have fewer providers per 100,000 residents compared to urban areas (see Figure 2), and residents of several counties still must drive more than an hour to reach a provider for in-person services.

Provider Age and Retirement Plans

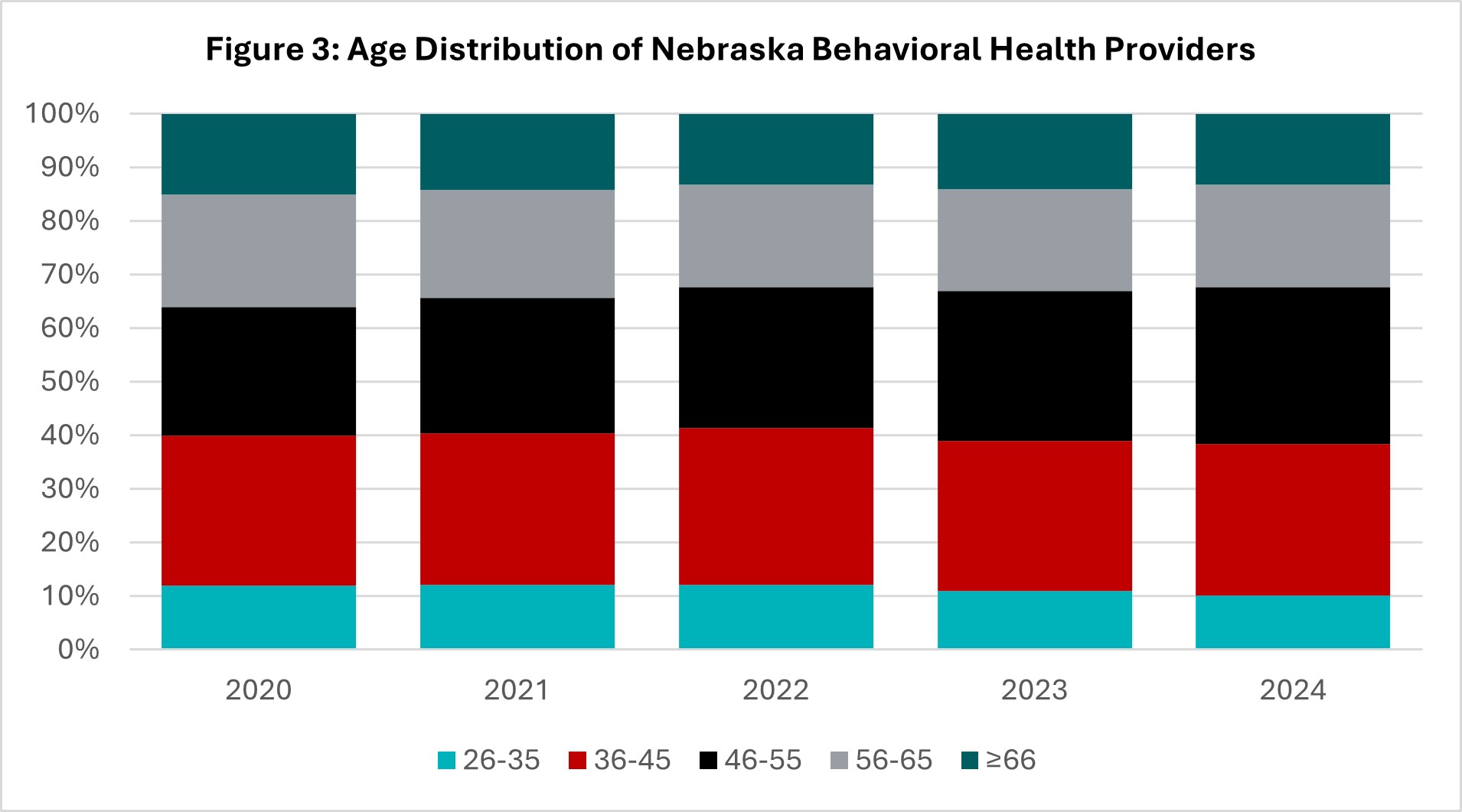

In 2024, 11% of providers indicated they plan to retire in the next 5 years. However, since 2020, the age distribution of the licensed behavioral health workforce has remained relatively stable, and the number of providers in the youngest age group (26-35) and the oldest age group (66 and older) was similar (see Figure 3). Therefore, provider retirement is not anticipated to negatively impact the total number of providers in Nebraska at this time.

Behavioral Health Service Needs

Several studies from 2023[6] show that approximately 1 in 4 Nebraska residents have behavioral health issues but many do not receive behavioral health care. A study focused on children and teens showed that 25% had one or more mental, emotional, developmental or behavioral problem (11% for ages 3-5; 27% for ages 6-11; 30% for ages 12-17), but 15% found it very difficult or impossible to receive needed mental/behavioral health care.[7] Similarly, 23% of high-school aged youth in Nebraska reported that their mental health (including stress, anxiety and depression) was not good most or all the time in the prior month.[8] Among adults aged 18 and older, 24% reported having a mental illness but 26% of those who needed treatment did not receive care.[9],[10]

Findings from BHECN’s Nebraska Health Workforce Partnership (NEBWP) 2025 Summit highlight that workforce shortages in rural areas, under-resourced communities, and for vulnerable populations such as children and adolescents result in long waitlists and fragmented referral systems.[11]

Interpretation and Recommendations

The data from 2010 to 2024 show a clear and positive trend in Nebraska’s behavioral health workforce. Overall, the number of licensed behavioral health providers increased by 49%, with growth across nearly every license type and meaningful expansion into rural areas. Forty rural counties experienced increases in behavioral health providers, demonstrating progress in improving access to care for Nebraskans living outside urban centers. These gains are encouraging and reflect the state’s sustained focus on behavioral health workforce development.

This growth also reinforces an important lesson: a successful behavioral health workforce strategy depends on both investment and intentionality. Nebraska’s experience demonstrates that there is no single solution to addressing workforce shortages. Instead, meaningful improvement requires a comprehensive, structured approach that considers every phase of a behavioral health provider’s training and practice.

At BHECN, we have developed the Nebraska Model for Behavioral Health Workforce Development, which provides this type of holistic framework. The Model includes six interconnected components—career awareness and preparation, training experiences, professional support, outreach and engagement, workforce research and evaluation, and policy and infrastructure—that together create a system designed to recruit, train, and retain behavioral health professionals. A workforce strategy built on this kind of model must be statewide, partnership-driven, and sustained over time through deliberate investment and collaboration.

While the results highlighted in this report are promising, it is essential to acknowledge that a complex array of factors shapes the behavioral health workforce. High demand for services can strain providers even as their numbers increase. Geographic maldistribution persists, and barriers to training and licensure—such as limited supervision opportunities—continue to impede growth. Furthermore, some challenges lie beyond what the Nebraska Model can address directly, including national labor trends, changing reimbursement structures, and broader socioeconomic factors. Yet, progress begins with intentional, data-informed action within the existing system. By building on the current foundation and remaining adaptable, Nebraska can continue to advance behavioral health care for all residents.

From this report, three key recommendations emerge to sustain and build upon this progress:

- Continue and expand investment in the behavioral health workforce. Strengthening and maintaining the existing infrastructure will support more training opportunities, improve the distribution of providers, and increase the number of graduates who choose to stay and practice in Nebraska.

- Increase paid supervision opportunities across all licensure types. Supervision remains one of the most significant barriers to achieving full licensure; expanding paid opportunities will accelerate the pipeline of qualified providers and reduce bottlenecks.

- Develop layered professional networks and partnerships. Establishing structured networks that connect students, trainees, and professionals at every level—and coordinating efforts among state agencies, academic programs, and behavioral health organizations—will reduce siloed work and maximize the impact of collective investments.

Nebraska’s commitment to tracking and analyzing its behavioral health workforce over time has positioned the state as a national leader. By maintaining this intentional, evidence-based approach and fostering collaboration across sectors, Nebraska can continue to demonstrate how thoughtful investment and coordinated strategy can lead to a more sustainable behavioral health care system.

Suggested citation:

Behavioral Health Education Center of Nebraska. (2025). The Licensed Behavioral Health Workforce in Nebraska: 2010 to 2024. https://www.unmc.edu/bhecn/research-data-policy/2010_2024_overall_snapshot.html

Footnotes:

[1] BHECN utilizes data from the UNMC Health Professions Tracking Service to determine the number and type of licensed behavioral health professionals who practice in Nebraska. We present hierarchical counts, where each licensed provider practicing in Nebraska is counted once, according to their highest license. Hierarchical counts allow us to examine changes in the total number of licensed behavioral health providers practicing in Nebraska.

[2] Beginning in 2026, BHECN will also track applied behavioral analysts, psychiatric pharmacists, and certified peer support specialists.

[3] Additional information about each profession is available in the BHECN brochure Pathways to a Career in Behavioral Health. https://www.unmc.edu/bhecn/career-pathways/index.html

[4] Given that LADCs also frequently hold a higher license, trends for LADCs are more difficult to determine from the hierarchical counts. Non-hierarchical counts for LADCs include all LADCs practicing in Nebraska, regardless of whether they also have a higher license.

[5] Poppert Cordts, K. M., Mone, V., Diao, J., Schneider, E., Doyle, M., Ratnapradipa, K., Watanabe-Galloway, S., Buckland, S., Horner, R. (Manuscript Under Review) Tracing Workforce Outcomes of In-State Behavioral Health Graduate Programs: The Nebraska Experience.

[6] Due to the lag between data collection and reporting, data for 2024 currently are not available. Due to changes in data collection methodology, comparisons between prior years and 2023 are not reliable.

[7] Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2025). Interactive Data Query: National Survey of Children’s Health (2022-present). https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse

[8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). YRBS Explorer. https://yrbs-explorer.services.cdc.gov/#/

[9] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2025). Interactive NSDUH State Estimates. https://datatools.samhsa.gov/saes/state

[10] KFF. (2025). Unmet Need for Counseling or Therapy Among Adults Reporting Symptoms of Anxiety and/or Depressive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.kff.org/mental-health/state-indicator/unmet-need-for-counseling-or-therapy-among-adults-reporting-symptoms-of-anxiety-and-or-depressive-disorder-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

[11] BHECN (2025). Nebraska Behavioral Health Workforce Partnership Summit 2025 Report.