UNMC is at the precipice of earth-shattering developments in the fight against HIV.

We are at that place thanks in large part to a brilliant chemist, whose impact may yet reach back to where he took his journey’s first steps.

Dr. Edagwa is making a mark in Nebraska, and on the world stage. But his story began on another continent, when a career in science wasn’t even a passing thought.

As college came to a close, a mentor hounded Dr. Edagwa about continuing his education abroad, but he was not interested. Finally, he agreed to take the GRE exam, but did not do well. And that was fine with him. He was done with school.

When his mentor failed to relent, he applied to just one American university, Louisiana State in Baton Rouge, hoping that would be the end of it when he didn’t get in. But then, he did.

It was not an easy transition. The culture. Communication, being understood. He was struggling. His project wasn’t going well. “I was so depressed,” Dr. Edagwa said, “that I almost dropped out of school.”

It had been four years in America, and he hadn’t published a single paper. He overheard his advisor saying she was worried he was going to have to start all over again.

He was so distressed he walked home, forgetting his car back on campus. He found himself sitting at the kitchen table staring at … table salt!

Eureka!

Dr. Edagwa envisioned the salt’s chemical makeup and it spoke to him, made it all make sense to him, and he walked back to the lab late that night, without having eaten, to give something a try.

He may still not haven eaten when he heard the next day that it had worked. How had he done it? “It’s a long story,” he said. But, the story was only beginning.

His experiment was a success. He was a scientist. He was going to graduate with his PhD.

The newly-minted Dr. Edagwa then answered a classified ad for a postdoc position, in Nebraska, at UNMC, working for a man named Howard Gendelman, MD.

“I saw the advert,” Dr. Edagwa said. “I said, ‘OK, this is what I want.’ ”

He felt Nebraska’s warmth from the moment he stepped off the plane in Omaha. This was the right place.

But, again, a tough transition. He at first struggled to express his ideas to Dr. Gendelman. “Just give me six months in the lab,” he recalled saying.

Before long, Dr. Gendelman grasped that Dr. Edagwa’s unique talents in chemistry could contribute to the realization of some very big things.

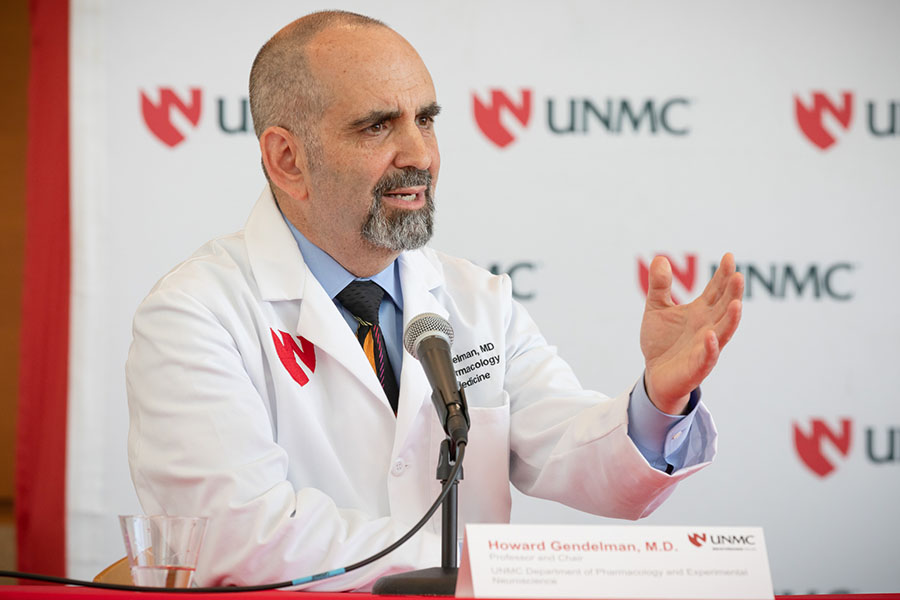

“I have been blessed to be a mentor, a colleague and an observer in a career that has just begun to blossom.”

Howard Gendelman, MD

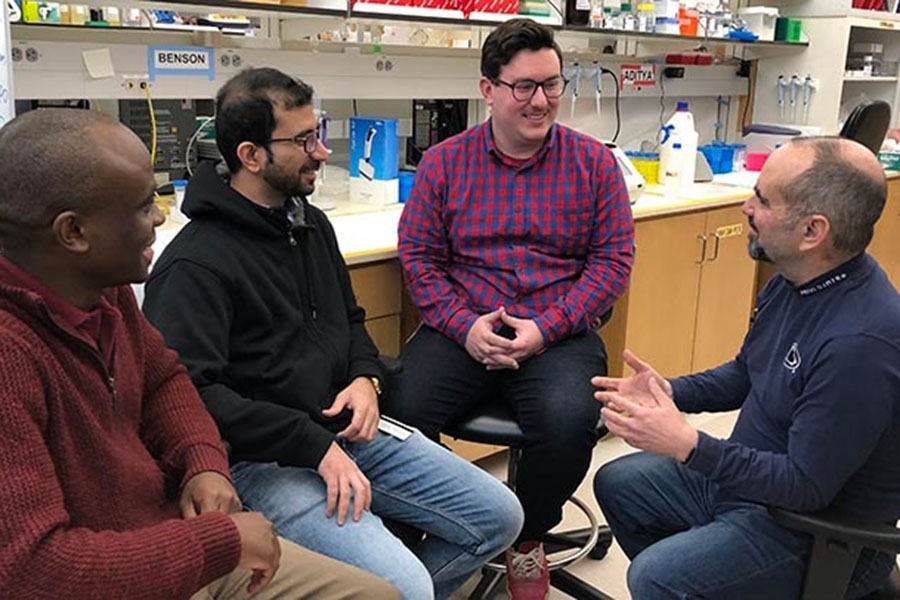

Howard Gendelman, MD, far right, talks in his lab with, from left, Benson Edagwa, PhD; Aditya Bade, PhD; and Brady Sillman, PhD.

“Obviously,” Dr. Gendelman said, “Benson is an evolving superstar.”

The two realized they worked well with one another. Dr. Edagwa, with his unique skill set, was a transformational addition to Dr. Gendelman’s decades-long labor in the fight against HIV.

HIV is now a livable, and largely manageable disease, in many countries, thanks to the work of Dr. Gendelman and others. We don’t hear much about it in this country anymore.

But, in Dr. Edagwa’s home country of Kenya, where resources are more limited, 1.5 million Kenyans are living with HIV. “Imagine,” Dr. Edagwa said, “more than half the population of Nebraska, living with HIV.”

Yes, HIV can be manageable, like it is here in the U.S. But, you have to take your pills every day. Every single day. Forever.

Does that sound easy? It’s not so easy. We’ve all forgotten to take our medicine. We’ve all been late on a prescription refill.

But more importantly, in some countries, there is the stigma.

A long-lasting, perhaps even once-a-year medicine would change everything: “The patient doesn’t have to worry about the social stigma of getting an HIV drug at a pharmacy, doesn’t have to worry about putting an HIV medicine on their cabinets, doesn’t have to worry about seeing a pharmacist, and can have the drug administered in a doctor’s office once a year,” Dr. Gendelman said.

“If you have something that is long lasting, that can be taken confidentially in a hospital setting,” Dr. Edagwa said, “that would make this disease go away.”

He likened it to storage, to keeping a large amount of something fresh and cold in the refrigerator, rather than having to keep buying individual drinks all day, every day.

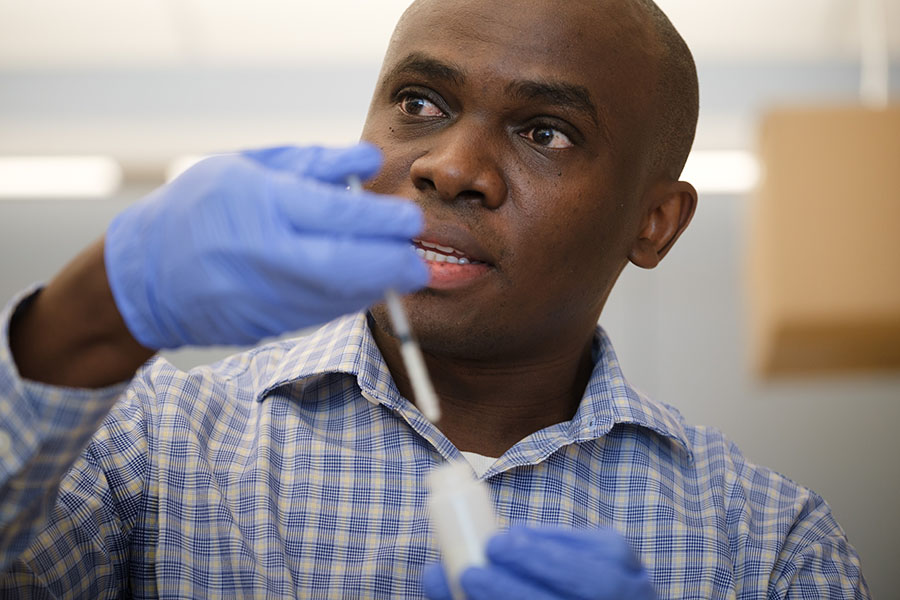

When he first proposed it, it sounded crazy. It would be doing the opposite of what had been done in the field for many years. “But in science,” Dr. Edagwa said, having learned years before with the table salt, “you’ve got to try things.”

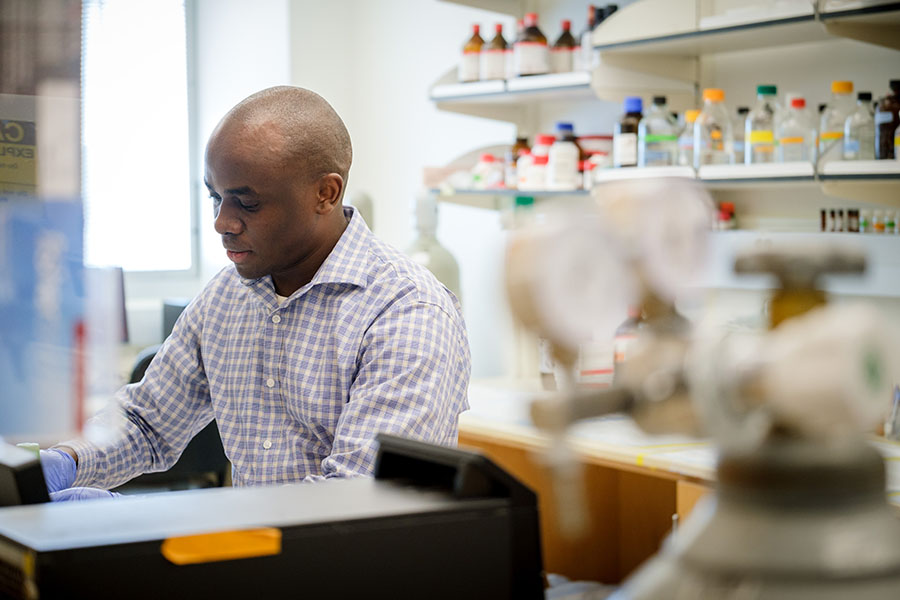

The secret to creating such a drug is chemistry.

Dr. Edagwa, working with a brilliant team of scientists under his and Dr. Gendelman’s direction, was able to take an HIV drug and modify it, change its chemical configuration, so it would stay in the body for up to a year. And in doing so, it could stop the virus from entering into human cells.

The treatment is not yet in human trials, but its future looks very bright.

This is possible, he said, because so many UNMC colleagues are working together. “There are many things they know, that I don’t know,” he said. “We try to complement each other.”

Everyone, including the environmental services cleaning crew that takes care of the lab, he said, is a crucial part of this team.

Jonathan Vennerstrom, PhD, one of UNMC’s most revered scientists, himself a chemist working to deliver drugs in fewer, more effective doses, calls Dr. Edagwa “an innovator.”

Why?

“For making drugs better than vaccines ever could be,” Dr. Vennerstrom said.

But, how did that come to be? Benson Edagwa was supposed to go to law school. He wanted to be a fisherman, then a farmer. He tried to get out of going abroad for further education in science. He struggled so badly in the lab as a PhD student, both he and his advisor started to wonder if he was going to have to give up.

How did he become not only a working scientist, but one of the world’s great scientific minds?

It happened, he said, when he finally realized that science was not an end to itself. Science was something you worked on in order to help people. Science could make a difference. “It’s not about getting good grades,” Dr. Edagwa said. “It’s not about talking. It’s about trying to solve a problem.”

As a scientist, he could do something to improve peoples’ lives. “It’s why my dad wanted me to be a farmer,” he said.

When Dr. Edagwa works on this project, it always comes back to Kenya. Mostly, it comes back to kids. Kids who, at young ages, are taking care of sick parents. Kids who have to go to work to support their families. Kids who are orphaned, scattered and separated from brothers and sisters, by the hundreds of thousands.

“These parents,” who are sick, he said, “have to make very tough choices. These parents, what kills them is the stress,” of knowing what is going to happen to their kids.

Dr. Edagwa thinks of all that could come to life, in Kenya, if only HIV were not hanging over everything. Of what a difference this drug would make.

He lost an uncle, to HIV. He’s lost several childhood friends.

He thinks of all that today’s children are losing now.

He remembers when he walked in their footsteps himself, all those years ago, when this journey first started. He’s still on that journey. He’s still walking. Every morning he wakes up, with miles to go.

He won’t stop until he takes this work, takes all that he has discovered, and brings it back to these children. Like a farmer working his fields, he’ll keep walking, and working, until he’s all the way home.