|

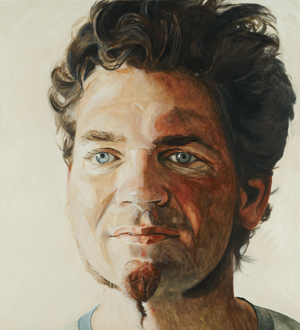

Kjell Cronn — who had a large tumor removed from his brain in 2006 — is pictured in this oil painting by Scottish artist Mark Gilbert. This among the many pieces that will be on display at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts from Dec. 12 through Feb. 21 as part of Gilbert’s “Here I Am and Nowhere Else: Portraits of Care” exhibit. |

Gilbert, a Scottish artist, composed the works that make up the exhibit while serving as UNMC’s artist-in-residence for two years.

During his time at UNMC, Gilbert drew portraits of many different patients and their caregivers.

The patients, who included children and adults, were dealing with a variety of health promotion and illness situations from childbirth to medical conditions such as AIDS, head and neck cancer or some sort of organ transplant. Most of the collection will be on display at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts through Feb. 21.

Today we feature an essay by Carl Greiner, M.D., professor of psychiatry and vice chairman for patient safety at UNMC, who participated in Gilbert’s project. Dr. Greiner’s work has included being a hospice physician and providing therapy for cancer patients. He has had a continued interest in the relationships between visual art, literature and psychiatry.

The power of portraiture to teach has been a longstanding, personal interest. During middle school in Berlin, I had several opportunities to view “The Man with the Golden Helmet.” The portrait provides a compassionate view of an older man who appeared to have stoically withstood adversity. His face has been deeply worn by the life he had lived. His eyes were focused down, away from the viewer. Despite the adversity, he maintained a sense of self respect. My interest was supported by an artist and teacher who had escaped from East Germany and had experienced significant adversity. She expressed the importance of truthfulness in art. Although I could not have articulated it at the time, the portrait provided a meaning to the faces of many senior American military personnel and some of the citizens of West Berlin. Each had witnessed more than an individual should have to endure. Significantly, most would not speak directly of their experiences.

The exposure to “The Man with the Golden Helmet” encouraged me to seek out other examples of portraiture. As a teacher, I have used perceptive portraits to teach clinical issues in psychiatry. During the first and second year psychiatric education section, medical students learn about personality and character. Portraits by Frans Hals, Van Gogh, and Picasso are useful in teaching about the expression of character.

Participating in Mark Gilbert’s “Portraits of Care” project was an opportunity to further study the role of portraiture as a teaching technique. His portraits of patients offered a novel way to capture the appearance of those who were coping with illness at either a single or series of points in their treatment. This article will consider how the portraits speak to an evolving sense of identity.

Caregivers (nurses, physicians and others) also were invited to have a portrait made. The rewards and stresses of caregiving can be seen in those faces. A psychiatric maxim is that caring for a patient leaves a specific imprint on the caregiver. For example, participating in a patient’s grief leaves an imprint of grief. Being involved in a healthy birth leaves an imprint of joy. Caregivers develop an accumulation of imprints, which from time to time, can be identified by an astute observer.

In examining the psychological factors in portraiture, six psychological processes are looked at with greater depth:

1. Empathy

2. Acceptance by others

3. Vulnerability

4. Internalization and self acceptance

5. Hidden feelings and secrets

6. Fear of rejection

Empathy is “to be listening or perceiving in a certain way so as to grasp some aspects of the patient’s inner experience.” Empathy is a capacity that can be improved through practice and teaching. Although empathy is a type of observation, it may lead to the feelings of sympathy and compassion.

By studying a keen portrait, the caregiver can increase his empathy. The patient’s posture, gaze, level of engagement and emotional tone can be clarified in a portrait. The caregiver may notice a patient’s quality that had not been previously appreciated. If a patient appeared withdrawn and “small” in his chair, the caregiver may feel increased permission to address the withdrawal.

As an extension of the example above, a cascade of emotional experiences can occur with greater caregiver empathy; being more observant of the patient can lead to the caregiver’s greater sense of sympathy and appreciation. The patient’s acknowledgment of the portrayed characteristics can generate an increased sense of engagement with the caregiver and increased hope.

A fundamental insight found in this kind of portraiture is the communal ownership of identity. We might initially imagine that our identity is simply our own possession. However, our identity is both in our possession and with those who have emotional connections with us. The interplay between our internal identity and external identity is active in each of our lives; the production of a portrait engages the patient in a new social process and can add a dimension to healing. The viewing of the portrait (by caregivers, friends, spouse, or significant others) becomes a potential psychological resource for the patient.

Those who have experienced major illness need to resolve “what do you think of me now?” An adult with a previously stable identity would still experience a re-working of identity. Who am I with these limitations? With a cancer diagnosis, my sense of an extended life is challenged. Will you still commit to me?

The experience of psychological vulnerability overlaps and typically extends beyond the time of physical healing from surgery or chemotherapy. “Coming to terms with grief” from physical losses are most intense for the first two years. In a similar manner, there is a slow process of finding personal acceptance and personal integrity. An important psychological outcome could be a mature sense of attractiveness in which “flawlessness” is not the standard. In the tradition of “The Man with the Golden Helmet,” being marked by life can lead to a more mature form of attractiveness.

Internalization is a process by which the patient incorporates the feelings of others. The caregiver holds a special place by providing direct care and frequently having a sense of the personal details of the patient’s life. The caregiver’s careful and sympathetic attention can be “internalized” by the patient as a source of self-acceptance.

A commonplace example is the importance of being “the apple of the parent’s eye.” This strong regard is considered to be foundational to a young child’s developing esteem. Older individuals are less prone to internalization but during times of stress or trauma, the individual becomes more sensitive to the feelings and regard of others. The caregiver is in a special position to become a “significant other,” providing valuable regard to a vulnerable patient.

A psychological dynamic that is particularly important is the tension between “the wish to be known” and the “fear to be known.” The “wish to be known” is the hope that one will be accepted with all of one’s faults and weaknesses. “The fear to be known” is the concern that one’s faults and weaknesses will be the source of rejection. Yousuf Karsh, the famed portrait photographer, felt one of his tasks was to determine the brief moment when his subject revealed his secret. I think there is a distinction to be made between a patient’s secrets (which the artist and caregiver should approach with respect) and an essential quality of the patient that may escape the untrained eye. Perhaps a more useful concept is the presence of hidden feelings.

Typically, a patient fluctuates on the degree of acceptance or rejection that he feels about himself and experiences from others. The challenge for the patient is to transform the unwanted changes in identity into a new, positive identity. An adept portrait can capture hints of these feelings (i.e. engagement or withdrawal from the artist).

One of the more controversial aspects of identity is the degree to which an individual actually knows himself. The Freudian tradition emphasized that there are unconscious issues that the individual may not readily know but which still influence behavior. An individual can have suppressed feelings that are kept beyond his usual recognition.

Imagine a middle-aged man, Mr. John Smith, who found that he has a cancer of the tongue. After the biopsy, his surgeon spoke directly and honestly with him. The surgery involved having a portion of his tongue removed and the resectioning of a few nodes in his neck. A course of postoperative radiation was recommended. Mr. Smith was relieved that his treatment would be less extensive than he feared although he was concerned if his speech would be clear.

The artist depicted Mr. Smith as an engaging man with a resolute face but who averted his eyes. Mr. Smith was pleased that he was portrayed as a strong man but he was surprised and initially uncomfortable by the portrayal of his averted gaze. His caregiver noticed the averted gaze and asked Mr. Smith about it.

Mr. Smith felt “off guard” and took a while to answer. He noted that he had a speech impediment when he was a youngster. Until he had speech therapy he did not look people in the eye because he was ashamed of his speech. This resolved by the time he was in second grade. Although the caregiver had taken a careful medical history, he was not aware of this issue in Mr. Smith’s life.

|

By having his averted eyes noted and discussed, Mr. Smith was gradually felt more comfortable about his surgery. His speech was not a problem and he was able to discuss his fears with his wife. As he discussed his concerns, he was able to incorporate his wife’s genuine affection for him. Over time, he ceased averting his eyes and began engaging others with a direct gaze.

How does a patient start to recover from having a major illness and its adversity? There are similar processes whether or not the illness brings a visible change in physical appearance. If there is a physical change, the psychological processing is likely to be more immediate. Illnesses that do not have an immediate, public presentation (i.e. testicular cancer in remission, for example) still have a major impact on the sense of self and identity.

As a psychiatrist, I would argue that no two people will have the same experience of illness. The psychological and social issues generated by being ill are highly dependent on the background and experiences of the patient. The caregiver will discover through intent observation how a particular patient is dealing with his particular illness.

Mr. Smith’s story reflects the psychological processes of refiguring identity after a major surgical intervention. Mr. Smith has psychological work to do in finding acceptance for his cancer and his relevant personal history. His portrait allowed him to address issues that he thought were hidden.

Typically, reconstruction of identity may be viewed as a social issue or a psychological issue. However, identity is strongly influenced by both. The patient’s work with the artist and caregiver is a social relationship that often provides emotional support. The creation of a portrait is a highly intentional activity; the artist’s engaging the patient is a commitment and a statement of worth.

Having a portrait made also is a psychological event. The psychologically perceptive elements of the portrait can be an invitation for the patient to consider a characterization, such as the averted eyes. The caregiver may see a “sense of resolve in the face” that the patient had not been aware was there. Or a look of bewilderment can confirm the patient’s sense of not yet knowing what to make of the injury. Simply acknowledging the bewilderment may provide the necessary invitation for the individual to seek out assistance from others.

An individual who has a major medical illness is more psychologically susceptible to the feeling of emotionally important individuals. The illness often generates a sense of guilt or inadequacy in the patient. The patient often feels a need to redress the self-perceived burden he has placed on the emotionally valued person. An astute observer might notice both the sense of guilt and the attempt to lighten the burden on the important person. An insightful and compassionate response to the patient will assist in lessening vulnerability.

For the caregivers, a portrait has a different function. Experiencing patients’ illness has a cost to the caregiver. The accumulation of emotional imprints from working with the ill can leave a look of gravity, determination, or compassion. The caregiver may be able to have a greater sense of empathy for their own situation. The caregiver may recognize that they have experienced fatigue or emotional hardening.

The power of the art has similarities to the power of words in psychotherapy. The portraiture may generate mixed feelings in the patient and their struggle with medical adversity. The range can include positive feelings toward demonstrated strength, anger about the losses and fears about acceptance. For the patient, the experience with illness can result in “the simple capacity to feel … losses, sorrow, shame, and have compassion.”

As in psychotherapy, the individual may not initially embrace the portrait. In that case, the portrait can serve as a source of further discussion about the consequences of the illness. The portrait can be used as a marker of how they were coping with their illness. The patient’s expression can suggest how well the illness has been accepted. If the portrait was received as disturbing, ongoing engagement with the patient can provide assistance with psychological resolution.

Several psychological consequences to caregiver and patient involvement in the portrait project are notable. An opportunity is created to form increased empathy and psychological understanding for both patient and caregiver. The patient finding increased self-acceptance can lead to a mature acknowledgment of personal strengths, weaknesses and physical changes.

An astute portrait provides a resource for asking meaningful questions. For both the caregiver and the patient, there will be the opportunity to learn about the psychological impact of serious illness, the importance of empathy and the development of an identity that acknowledges the illness. Acknowledging the importance of caregivers in providing a meaningful response to illness will be an ongoing aspect of clinical education.