|

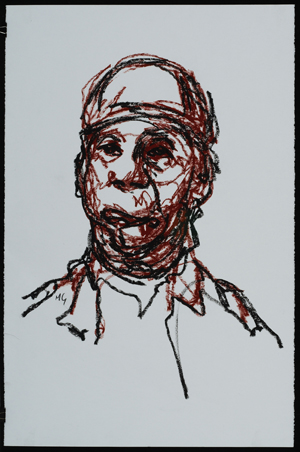

This drawing of Anthony, a head and neck cancer patient who participated in Mark Gilbert’s project, is among the many pieces that will be on display at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts as part of the artist’s “Here I Am and Nowhere Else: Portraits of Care” exhibit. |

Gilbert, a Scottish artist, composed the works that make up the exhibit while serving as UNMC’s artist-in-residence for two years.

During his time at UNMC, Gilbert drew portraits of many different patients and their caregivers.

The patients, who included children and adults, were dealing with a variety of health promotion and illness situations from childbirth to medical conditions such as AIDS, head and neck cancer or some sort of organ transplant. Most of the collection will be on display at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts through Feb. 21.

Today we feature an essay by Michael J. Krainak, an art critic who composed the following essay for the exhibition catalogue.

It is a television star vehicle for Holly Hunter, a Tom Petty hit and YouTube fave, and the subtext for many Christian evangelical churches. Yet, nowhere does the label, “Saving Grace,” seem more applicable than to artist Mark Gilbert’s exhibit at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts: “Portraits of Care,” side-by-side images of the general patient populations and their caregivers at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. Gilbert created this work while in an extended residency at UNMC beginning in 2006 until August of 2008. The artist was commissioned to create work that would “unlock dimensions of the therapeutic relationships that are difficult to articulate, yet form the foundation of the art of care,” according to the project’s official statement.

The portraits in this exhibit, with all 50 individuals who sat featured in this catalogue, were part of a research project initiated by Virginia Aita, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of health promotion, social and behavioral sciences, and Bill Lydiatt, M.D., a professor and director of the department of head and neck surgical oncology, “for the purpose of professional discourse, scholarship and public education.” Yet, from the beginning, project directors and Gilbert were determined that the images be intended not as documentation but as a means of observation, interpretation and expression. Which is to imply that these are not ordinary portraits. If indeed the “art” of “care,” they raise such questions as: Do they convey something other than character or personality? If so, what? A state of being? A state of health? And, for that matter, is it art?

Gilbert’s residency began after UNMC and the UNO College of Communication, Fine Arts and Media hosted his “Saving Faces: Art and Medicine” exhibit in 2006, which began as a similar project at the Royal London Hospital in 1999. This initial significant and controversial exploration in the relatively unknown and unexplored fields of medicine and art featured 42 paintings, from over a collection of 100, of medical patients in the process of surgical restoration of their facial deformities caused by cancer, trauma or congenital defects. Once viewers got over the initial shock of the show’s graphic depictions, they often became absorbed into the patient’s spirit of survival.

This transcendent response was due largely not only to the success of the reconstructive surgery but to the skill of Gilbert’s humanistic portrayal of each subject’s ordeal, including the sitting itself. As this critic wrote then in a published review: “Art and medicine may seem like strange bedfellows, but this exhibition is proof positive that sometimes beauty is also in the face of the holder of both scalpel and brush.”

“Portraits of Care” carries a different sort of emotional baggage for subject, artist and viewer, as well as highlighting its own relevance and aesthetic. It features oils on canvas and aluminum, charcoal drawings, monoprints, one woodcut and one photogravure of subjects with serious illnesses, as well as children and maternity patients. It also includes their caregivers from what Dr. Aita describes as a “community of care” — nurses, doctors, family members, a chaplain, an administrator, and a custodian. Though the work has proven to be a beneficial part of UNMC’s research into health care, Dr. Aita was adamant that, as with “Saving Faces,” these portraits should be seen by the public as an art exhibit. To that end she met with Bemis Director Mark Masuoka and Curator Hesse McGraw and selected the works you see both in the show and catalogue. …

Ironically, the sitters adapted more quickly to the dynamic and its circumstances than Gilbert himself. “It is an exhibition that with my own personal health anxieties I would find very difficult to visit if I were not the artist,” Gilbert admitted. “But from an artistic perspective it is the challenge and risk that drives the project. It is not a subject matter that sits comfortably with me at all, neither was ‘Saving Faces.’ But work of any substance has to take you out of your comfort zone. I have never had to deal with acute illness with myself or loved ones, but it will come to all of us, and that makes this show relevant to all I hope.”

“Hope” is the operative word here as patients and caregivers adjusted to their own anxieties as the sittings progressed. Gradually they too became part of a healing process perhaps more spiritual or emotional than physical. More than saving faces or even lives, the portraits suggest an existential confirmation of their condition or their role. A rare state of grace without judgment that varies from acceptance and humility to sacrifice and mercy. At times the expressions are tenuous and uncertain, but they are also unflinchingly honest and natural.

“I have tried also to avoid obvious signals or symbols that explain whether one is a patient or caregiver,” Gilbert said. Or both for that matter as in the case of Jason, an enigmatic individual with a disfigurement due to facial surgery who is also a caregiver, an employee of the medical center. Perhaps better than anyone, Jason faces the viewer with the fullest expression of the exhibit’s universal theme, that all have been, or will someday be, a patient and a caregiver. As a virtual “poster boy” for the show, Jason shares a commitment to the research project with the others, some of whom came to it reluctantly.

“A Native American (Anthony) I worked with who had surgery for cancer initially was opposed to the whole concept of a portrait,” Gilbert said, “believing it steals part of the sitter’s identity, a traditional belief of his tribe. Yet, now he feels the pictures of him and his surgery are a testament and record of his situation. He also feels that they demonstrate the trials and struggles he and others have to go through in their efforts to recover. Many of the patients talk about the process of sitting as a way of ‘giving back’ or ‘doing good.’ I think they appreciate more than many that these are not idealized or sanitized images.”

In fact, Gilbert has said that these portraits are “quite scary,” not for the viewer as in the initial Grand Guignol response to “Saving Faces” but for him as artist. “I have found it much harder to work on these images,” he said. “Whether it was lack of confidence or whatever. As time has gone on I have felt more comfortable with the subject, but I still find it an uneasy experience to work with acutely ill. And you feel an additional responsibility ‘to do justice’ to them.”

Another concern of Gilbert’s is how the “art world” views these portraits, as either fine art or the diminished applied art, which refers to the application of design and aesthetics to objects of function and illustration, as in the fields of science, medicine, fashion and architecture among others. The issue regarding his work was first raised in a September 2006 artblog by Roberta Fallon who favorably reviewed four “Saving Faces” pieces at the Klein Art Gallery in Philadelphia but questioned, “Is it art?” When Fallon concluded that the portraits were applied art, merely “therapeutic for the patients and illustrative for the viewer,” artist Dan Schimmel, the director of the Klein, responded eloquently. He reminded the reviewer that one significant “application” of all fine art is “to let us observe, understand and address ourselves outside our routine experience … so we can come to our own conclusions based on a full experience that engages all our senses. How many art exhibits do this anymore?”

|

|

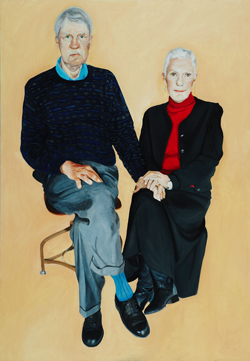

These two pieces from the “Portraits of Care” exhibit are examples of some of the techniques Gilbert used to create his images. |

Yet, as similar as “Saving Faces” and “Portraits of Care” are, the latter has its own aesthetic, a matter of both process and vision. Everyone you see here went through a series of sittings, many over a period of two years. While all the drawings are done completely from life, the oils on canvas were created from photos Gilbert took during sessions, their procedures in the OR or delivery room. Though the small oils on aluminum were also done from life, the artist said he would have painted the large oils in this manner, but “that is a big undertaking for any model at the best of times. Many would have been physically unable to sit for the number of times and length required.” As it was, several sat often over the period at times that varied from an hour and one half to four or five hours.

“Portraits of Care” are revelatory in their power to interpret the human condition in a social arena that heretofore has only begun to get recognition. Gilbert has accomplished in the medical field what two early 20th century artists, Henry Tonks and Käthe Kollwitz, did in their fields of observation and interpretation. Kollwitz (1867-1945) was a German painter, printmaker and sculptor whose drawings and prints, as in “Woman with her Dead Child” and “Self Portrait with Hand on Brow,” revealed the victims of poverty and war particularly among women and the working class. Tonks (1862-1937) was a British artist and surgeon whose work in hospitals and on the WWI battlefield, such as “Man by a Woman’s Bedside” and “An Underground Casualty Cleaning Station,” often had a medical theme, especially the wounded, ill and hospitalized.

Besides sharing their thematic concerns, Gilbert’s portraits vary in style from Kollwitz’s deeply involved expressionism to Tonk’s studied naturalism, no doubt adjusting to each individual and their own personal narrative. Overall, this current work, with notable exceptions, is more subtle and complex than the bolder “Saving Faces.” With their scars, disfigurements and injuries “superficially obvious” as Gilbert described them; those portraits dared one to look away even as they burned into the imagination, exhausting one with sensory overload. I earlier described these larger-than-life close-up paintings as “mythical masks that echo universal physical and psychological trauma.”

Yet, their size, palette of pure hues and rawness tend to emphasize primarily the physical and thus, ironically, distance viewers and their sincere, sympathetic points of view, as if to say “here, but for the grace of God, fate or dumb luck, go you.”

Largely without the benefit of visual clues to the sitter’s situation and/or station in “Portraits of Care,” viewers nevertheless are more likely to be empathetic. Not only because of the shared universal connection previously mentioned, but because these images provoke us more by what they don’t say or show while drawing us into their “stories.” We don’t need to know the specifics of their back stories in order to identify with their desire to be where they are at that time and place, in spite of any uncertainty. But, none of this would have been as accomplished or deeply felt without the enlightened nuance and fragile beauty of Gilbert’s artistry.

Gilbert works intently to adapt a style or technique that best interprets less a condition and more a moment and mood or even the state of mind of his subjects, especially the patients. This is particularly true of his charcoals, oil sticks on paper and monoprints, when the moment is now, natural and spontaneous. Anthony, who deals with head and neck cancer, is a perfect case as he appears in all these mediums in various stages of his treatment and illness. Each portrait reflects this, as well as his attitude, in the artist’s signature, minimalist style.

In one oil stick drawing, Gilbert resorts to aggressive contouring and shadowing in red and black to convey a proud Anthony who wears his bandages like red badges of courage, all the while determined to be included in his own therapy as well as the project. In sharp contrast is a large charcoal on canvas image of him, more peaceful and meditative, whose head bandages now sport cartoon figures. Gilbert softens the edges here in a process of blending, blurring and erasing, often by hand. The result is an image of more depth, especially in the face, which effectively mirrors Anthony’s introspection. Another charcoal pictures him bright-eyed, upright, almost confident.

Yet another study in contrast are two charcoals of the previously mentioned Jason (sinus cancer), a patient and caregiver. Gilbert’s mark-makings here are dark jabs, scratches and slashes that fittingly nail a virtually defiant Jason, who faces the viewer, arms folded and with full-figured strength. It is as if Jason were saying, cliches aside, “My illness has made me stronger.” He knows why he is there and understands his role: battling his cancer by helping others.

All of the caregivers hold a special place in this show for the project directors, because, as Dr. Aita points out, “I am adamant that the public see and respond to the exhibit because they will have a lot to say about health care that is stimulated by their responses to the portraits.”