For years, health care professionals believed that all measures taken in intensive care units (ICU) were for the patients’ own good.

Patients were tied down so they couldn’t pull out their lines or tubes. They were put on machines to help them breathe. Intravenous lines were inserted to deliver life-saving medications. Powerful drugs immobilized them.

The drugs gave patients the desired amnesia about the trauma they faced, but it also gave them something less desirable – delirium.

“As a nurse,” said Michele Balas, Ph.D., assistant professor in the UNMC College of Nursing, “I remember thinking, ‘I don’t want them to remember anything we’re doing to them.'”

While the ICU keeps patients alive, it turns out the delirium can have lasting, even deadly effects. Delirium often causes a loss of functional and cognitive ability such as an inability to balance the checkbook or help kids with homework. And older adults are more likely to go straight from the ICU into nursing homes or other long-term care facilities.

Though all of these measures are done with the best of intentions, the long periods of immobility and ensuing muscle atrophy, along with the drugs, not only erase memory, but also distort reality.

“They think they’re crazy,” Dr. Balas said. “They’re embarrassed to talk about it.”

But Dr. Balas is talking about it.

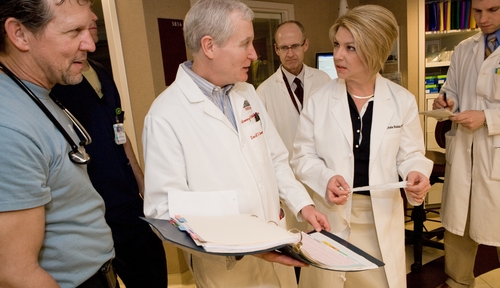

Dr. Balas and her interdisciplinary team, which includes William Burke, M.D., professor of psychiatry, are trying to find a way to decrease or even prevent ICU delirium.

The goal is, for a little while each day, to let patients wake up, get them off the drugs, take off the ventilators to let them breathe on their own, get them up and moving, and look closely for signs of delirium to address it in the early stages.

But it won’t be easy. It takes a team effort – all members must talk to each other and appraise the patient’s condition beyond meds and vital signs.

“The problem is changing the culture,” Dr. Balas said. She admits it herself: “Patients are much easier to take care of when they’re down.”

But we never fully realized, until lately, all that was really going on, while they were down.