Jennifer Harney, M.D., of Aurora, Neb., is an example of how a medical discovery and Nebraska health professionals impact lives. She will graduate this summer from residency training at UNMC and plans to practice family medicine in Aurora at Memorial Community Health.

Dr. Wiltse’s impact

Julie Luedtke, program manager in the Newborn Screening & Genetics Program for the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services, said Dr. Wiltse was well-known.

“We considered Hobart Wiltse the godfather of newborn screening in Nebraska,” Luedtke said. “He was not only a great physician he was a kind and dedicated advocate and adviser for the newborn screening system for many years.”

It was the care of her physicians who saved her life and influenced her to become a physician.

Her journey started as a newborn when she tested positive for phenylketonuria (PKU).

“If I didn’t adhere to a special diet, the phenylalanine would build up in my bloodstream and in my brain and cause irreversible, severe brain damage,” said Dr. Harney, who also graduated in 2011 from UNMC’s medical school. “PKU causes severe cognitive impairment — seizures and developmental disabilities.

“I can’t break down phenylalanine,” she said. “That means I can’t have regular protein since it’s in all protein — a building block. My life has consisted of being on a really strict, low-protein diet. I can have about six grams of protein a day. A typical adult eats about 50 to 60 grams.”

It’s estimated that she and hundreds of other Nebraskans are the beneficiaries of a Nebraska law passed 50 years ago that mandated a screening test for newborn babies for a number of inherited disorders such as PKU.

While growing up, Dr. Harney had to make weekly visits to her pediatrician for blood tests. At least once a year she would go to Omaha for a specialty visit at the metabolic clinic at the Munroe-Meyer Institute at UNMC.

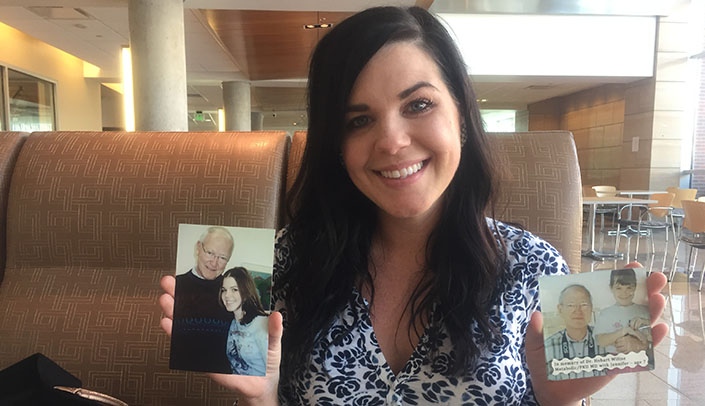

That’s how she met the late Hobart Wiltse, M.D., a pediatrician/metabolic specialist who was instrumental in getting Nebraska to implement the screening test for inherited disorders in newborns.

“If it were not for him, and the treatment they gave me, I would be in a wheelchair having seizures,” Dr. Harney said. “He was a big inspiration for coming into the medical field. He changed patients’ lives, families and the people he taught — the students, residents, his co-workers — that just really stuck with me and that’s the doctor I hope to become.”

Dr. Wiltse told her that he always wanted one of his PKU patients to become a physician and that he thought she would be the first one.

Research continues to find ways to make life better for patients. Dr. Harney participated in a clinical trial for three years headed by UNMC’s William Rizzo, M.D., before she became pregnant. A medication enabled her to eat anything she wanted. The medication has been submitted for approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

She said approval would be huge for patients with PKU.

Dr. Harney and her husband welcomed their firstborn last October and got good news — their son, Finn, is a PKU carrier, but he does not have the disorder.

This is a GREAT story! I worked with Dr. Wiltse and his passion and compassion for his patients and making sure newborns were tested was his priority. He was dedicated to the students and residents, and educating them about PKU and other metabolic diseases. He would be so very proud to know that he was right about Dr. Harney becoming the first PKU patients to become a physician! He is missed by so many. Congratulations Dr. Harney!

I'm so glad to hear this story of Dr. Harney's good health as well as professional and personal happiness! One more example of the importance of our University to the state of Nebraska and beyond!