When his father was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 1998, Sunil Hingorani, MD, PhD, was exquisitely placed to have the best possible impact on his father’s cancer struggle.

He was a clinical fellow in gastrointestinal oncology at the Dana Farber Institute. He also was doing post-doctoral research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in a laboratory that was studying the gene that was the main driver of pancreatic cancer. But he found he could do little.

“We essentially had no chemotherapeutic agents that were effective,” he said. “Gemcitabine had just been FDA approved for the treatment of pancreas cancer. But we already knew it didn’t impact survival much, if at all. The reason the FDA approved it was primarily because of some symptom relief and quality of life improvement, but it really didn’t prolong survival significantly.”

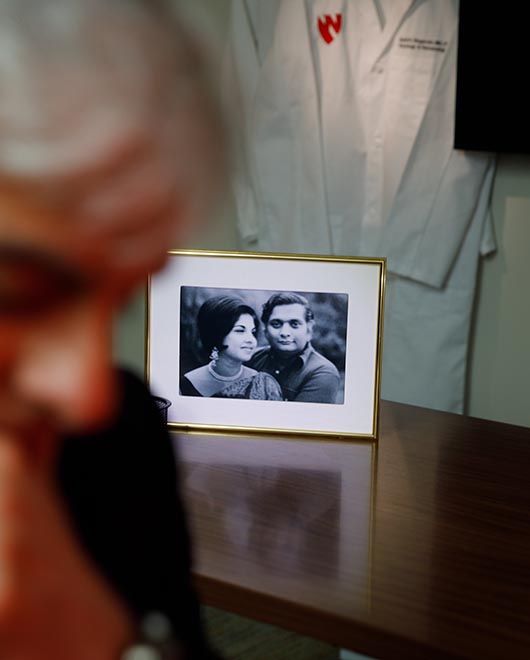

When Dr. Hingorani speaks of his father, a listener can hear the respect. The pride. The love.

Ram H. Hingorani was an engineer who attended the prestigious Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. It was during his studies at RPI that he noticed something about his fellow students – their sense that the world was wide open.

“They were filled with thoughts and ideas of all the things they could do,” is how he explained it to his son.

“Growing up in India, you understand from a relatively young age where the boundaries are — boxes are put around possibilities and avenues of where you might progress,” Dr. Hingorani said. “Here in America, there was no such thing. He and my mother decided they wanted that for their children.”

So they came to America, where they started an engineering firm and where Dr. Hingorani — the eldest of three children — fulfilled his father’s American dream, studying at Yale, studying at Harvard, getting his MD, his PhD, and prestigious fellowships.

But when Dr. Hingorani talks about this part of the story, there’s no sense of pride.

“I couldn’t do a damn thing for the one person in the universe that I perhaps cared about the most. The man who gave me everything and had never once asked me for anything.”

Pancreatic cancer is an insidious thing.

Researchers don’t get to see the polyp stage, as they do for colon cancer. Or the ductile carcinoma in situ, as they might in breast cancer.

“One of the great problems, both clinically and scientifically, is that pancreas cancer almost always presents at very advanced stages,” Dr. Hingorani said. “In the majority of cases, it’s already metastatic, and it’s certainly not something that can be addressed surgically. So, you have an advanced disease in which the patient is likely to live weeks or months.

“That’s challenging for the clinician. Certainly, it’s terrifying for the patient and the family. But it also means, scientifically, we have no real understanding of how the disease arose.”

“The pancreas itself is very difficult to get to,” Dr. Hingorani explains. “It’s dangerous to biopsy, because when you stick a needle in the pancreas, it’ll release the digestive enzymes, which can then leak locally into the tissue and then begin to autodigest the pancreas. Which causes more enzymes to leak, resulting in pancreatitis.”

So the sort of serial biopsies routinely done on patients, as in a colonoscopy, cannot be done on a pancreas. Preventive care is not merely impractical — it is almost impossible. When the cancer is discovered, it is almost always too late to treat it.

Deadly numbers

Most cases of pancreas cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage. According to the National Cancer Institute:

people will be diagnosed in 2023

will die of pancreas cancer in 2023

of patients will survive 5 or more years after diagnosis

When his father got sick, Dr. Hingorani discovered that there was a world of difference between being a clinical provider of a cancer patient and being a family member.

“It was eye-opening,” he said. “I’d always thought of myself as being a fairly empathetic physician — caring and attuned to the patient’s needs. I realized that, in going through this process — at the hospitals where I trained — the systems are designed for the convenience of the providers – the surgeons, the oncologists, the nurses, everyone who takes care of patients. The system is built around their convenience, not the patients’.”

It was a realization that would have a great impact as he continued in his career. But first, Dr. Hingorani had to bring his father home to die.

Dr. Hingorani was literally across the street, but unable to make the appointment, when physicians told his father that it was time to go home.

“You don’t want to die in a hospital,” they said.

When Dr. Hingorani learned his father was going to be discharged, he drove his car around to the back of the hospital and popped the trunk. One of his father’s nurses — he won’t say who — met him there.

“She couldn’t do this today, but she basically loaded the car up with all the kinds of supplies and things that I would need to take care of my dad at home,” he said.

“When you started as a clinical fellow at the Dana Farber back then, you were paired one-to-one with a nurse who essentially becomes your nurse for your entire time,” he said. “Those nurses are incredible. And I probably learned more about oncology care from my nurse than any of my teachers.”

Dr. Hingorani went back to Connecticut with a trunkful of medical equipment and a goal. His father was concerned about the future of his company and its employees, many of whom had been with him for more than two decades. He wanted a new owner who would continue the company and keep all the employees.

“That’s what he asked me,” Dr. Hingorani said. “Could I keep him alive long enough for him to do that? And I told him quite honestly, I didn’t know, but I would try.”

Four months later, on April 2, 1999, and from a bed on the first floor of his house, Ram Hingorani completed the sale of his company, on his terms, ensuring the security of his more than 70 employees.

It was 11:30 a.m.

Three hours later, he was gone.

When Sunil Hingorani arrived at UNMC in May 2022, he came with a stated goal — to cure pancreatic cancer within a decade. He came with the tools: mouse models that he helped develop, which are now so accurate and faithful to the human cancer that pathologists say they can’t tell them apart from human samples. And he came with a diagnosis of a main problem.

Unlike other cancer cells, which reach into the body’s circulatory system to grow, a pancreas cancer cell will actually decrease its blood supply as the tumor grows. So chemotherapy, which is delivered through the circulatory system, “never gets into the tumor in sufficient concentrations,” Dr. Hingorani said.

His laboratory made this discovery in 2012 and described its mechanism. This was big news, information that could shift treatment approaches. “It provided both a very simple and powerful explanation: these tumors weren’t intrinsically resistant. They just never got exposed to a high enough concentration of the drugs.”

Excited, Dr. Hingorani called his mother. He was keeping her informed on his work, of course. The whole family had skin in this game, after all.

“She lost the love of her life,” he said. “I mean, I’m still angry to this day, and that motivates everything I do, about the fact that I wasn’t able to help my father. But if you think I’m angry, you should talk to her.

“I have to give her progress reports periodically about how we’re doing. So, I described this result to her, this discovery and that in the scientific community, we were getting a lot of credit for it.

“My mother listens to this and she says, ‘OK, so let me see if I understand.

“’First of all, you’re an oncologist, right? And you give chemotherapy to your patients?

“’So, you’re telling me that the drugs you’ve been giving, you’re saying that it went to every tissue in the body except the cancer you were trying to reach?’

“I said, ‘Yes, mom. That’s right.’

“And then she says, ‘And you’re proud of yourself?’

“And I said, ‘Uh, no mom, I guess I’m not.’

“And she said, ‘That’s right. Why don’t you get back to work?’ And she hung up the phone.”

Sunil Hingorani, MD, PhD, leads a weekly pancreas multidisciplinary conference at the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center. At left is Christina Hoy, DNP, clinical program director for the Pancreatic Diseases Specialty Clinic in the Pancreatic Cancer Center of Excellence.

There are several reasons that Dr. Hingorani brought his work to UNMC.

Part of the reason was his father’s heroic, four-month battle to complete the sale of his company, and the lesson it taught.

“That has remained to me a powerful reminder of the importance of the patient’s mindset,” Dr.

Hingorani said. “I’ve seen that over and over again. I always ask at the first visit: What are the patient’s goals? What are the most important things to them? Are there some specific milestones or lifetime events that they’re working toward?

“The point being that you put the patient in the center of everything you do, of everything you build and of everything you study.”

He sees that emphasis at UNMC, Nebraska Medicine and the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center.

“There’s a level of commitment, by the state, state legislature, the University of Nebraska Medical Center, key physicians and philanthropists, within the institution and in the community. There are people who have been affected deeply by this disease in the same way that my family has.”

In May 2022, Dr. Hingorani addressed the media at an event marking the partnership of the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center and the Berenberg Invitational Golf Tournament.

He thanked the tournament and its sponsors for providing significant research funding to the cancer center. And then he delivered what amounted to a mission statement.

“You root everything in the patient,” he said. “There are discoveries being made that will make a difference at some point, but only if your goal is to apply those discoveries to the care of the patient, only if you’ve decided that is what your aim is.

“There is tremendous talent here, there is tremendous science, tremendous clinical medicine, but the most important thing is that there’s that ethos of ‘the ability to do this.’”

The ability to find a cure for pancreatic cancer — that’s what he sees at the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center.

“All the pieces are here,” he said. “A director of the (Pancreatic Cancer Center of Excellence) can provide the catalyst, that impetus, that stimulus.

“And I’m honored to be that person.”

Very inspiring story of your father, Sunil. thrilled to have you here at UNMC..

I lost my mother just about two years ago to acinar cancer… a form of pancreas cancer.

I’m angry too. So, thank you for your work and your passion from all of us who lost someone too soon.

I’ve been been battling this terrible disease for 6 years. Stage 4 pancreas cancer. Been taking chemo unmc. Great nurses at village point. Praying for a cure.

I am thankful for the work being done at a world-class organization like UNMC to fight Pancreatic Cancer. I appreciate the efforts and dedication of people like Dr. Jean Grem, Dr. Hingorani, and Dr. Paul Grandgenett. Keep up the fight!