|

The two key UNMC physicians in the procedure — Drs. Jean Botha (left) and Brian Stevens (right) — flank Shirley and Leonard Goldstein, an Omaha couple who has contributed money in support of UNMC’s diabetes research programs. |

Unlike other children, though, little Berlyn has spent much of her young life in and out of hospitals. She recently became the youngest patient known to undergo an autologous islet transplant.

The innovative procedure occurred April 6, at The Nebraska Medical Center, performed by a talented team of transplant surgeons and scientists under the leadership of R. Brian Stevens, M.D., Ph.D., and Jean Botha, M.D.

“This was quite an extraordinary process which required a truly multi-disciplinary approach,” said Dr. Stevens, director of the islet cell transplant program at UNMC and The Nebraska Medical Center. “This isn’t a procedure that would normally be performed on such a young child but Berlyn’s struggle with pancreatitis was rapidly becoming more and more critical.”

In severe cases of pancreatitis when the condition becomes chronic, the only real solution is to remove the entire pancreas. Dr. Botha, director of hepatobiliary surgery at The Nebraska Medical Center and assistant professor of surgery at UNMC, recommended the surgery to Berlyn’s family. “Her flare-ups were lasting days, even weeks, causing terrible pain,” Dr. Botha said. “The disease was resulting in almost weekly admissions to the hospital. This would have resulted in progressive fibrosis and scarring of her pancreas. Eventually it would no longer function or produce the insulin needed to regulate sugar levels in her body.”

As they considered the most effective course of treatment, Drs. Botha and Stevens also determined Berlyn would be a good candidate for the islet transplant.

“Without the transplant, we were certain this little girl would become a ‘brittle diabetic’ meaning she would have the most severe form of diabetes – one that is exceedingly difficult if not impossible to manage. It was a very frightening prospect considering she’s just 3-years-old,” Dr. Stevens said. “In removing the pancreas and infusing islets into the liver, we hoped at the very least to keep her blood sugar levels better controlled.”

|

Berlyn Alfredsen with her mother, Lena, and sister, Liberty. |

The science behind this procedure is fascinating, almost like a chapter out of a science fiction novel. Berlyn’s transplant was autologous, meaning she received her own cells. This carries a distinct advantage — since the tissue was coming from her body, she would not need to take immunosuppressant medications to fight rejection.

Once in the operating room, Dr. Botha removed the little girl’s pancreas. The diseased organ was then transferred to a special processing lab where it was slowly dissolved, allowing specialists to extract microscopic pieces of remaining healthy islet tissue.

The environment in which this process occurs is vital to the procedure. Since the tissue is being removed and processed before being returned to the patient, it must be handled in an extremely hygienic and pure atmosphere known as a Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) facility.

“When we perform a procedure such as an islet transplant, we must maintain the viability of delicate living products – in this instance, the tissue and cells,” said Theodore Rigley, director of operations and process development in UNMC’s Islet and Cell Processing Laboratory. “Quality control rests largely in our ability to control the environment in that particular lab. This includes a higher standard for air quality and climate control in addition to strict requirements for cleanliness, purity and safety. There’s also increased monitoring and documentation.”

At this time, The Nebraska Medical Center’s GMP is considered a temporary facility. The space is small and capacity is limited. Work is already in progress on what’s called a current GMP (cGMP) Transplant Production Facility to be permanently located in the Academic and Research Services building at 42nd and Emile streets. The new facility will house specialized areas for processing organs, tissues and cells into grafts for transplantation.

“The Nebraska Medical Center and UNMC are known for innovation, expertise and cutting-edge treatments. A permanent GMP facility is critical in not only allowing us to continue what we do, but also to take it to the next level for our patients,” Dr. Stevens said.

|

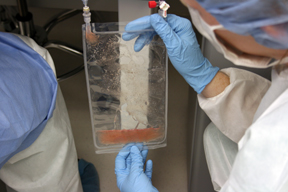

Physicians hold a bag containing islet cells. |

“The patient stays on insulin as the graft begins to function, but as the weeks go by the idea is to greatly diminish his or her reliance on insulin injections,” Dr. Stevens said.

Three weeks post-transplant, there were signs of that happening for Berlyn. “She’s receiving quite a bit less insulin,” said her mother, Wendy Alfredsen. “The islets are kicking in and things are becoming more manageable.”

Nothing has been easy for Berlyn and her family. Many of her health problems are thought to be connected to her birth mother’s use of narcotics and opiates during pregnancy. When Berlyn was 3-months-old, Alfredsen and her partner, Lena, adopted the infant and her older sister, Liberty.

“Berlyn has always had eating problems and growth problems,” Alfredsen said. “At 3 months, she weighed 5 pounds, 10 ounces. That was only about 2 pounds more than she weighed at birth.”

As the infant’s condition grew progressively worse, the Alfredsens traveled the country looking for answers. “She’s a huge mystery. Anatomically, everything looks fine but she can’t tolerate even a few drops of liquid in her stomach.”

While the islet transplant solves the immediate crisis of Berlyn’s pancreatitis, the Alfredsens know their medical journey is far from over. Their little girl will eventually be listed for a multiple organ transplant. “She’ll need a small bowel, liver and pancreas at some point,” Alfredsen said. “It’s inevitable.”

As they prepare to head home to Colorado, the Alfredsens share special thanks with everyone at the Ronald McDonald House. They say it became a “home away from home” throughout their stay in Omaha. “We are so appreciative of the Ronald McDonald House. Being away from home and work, we could not support two households,” Alfredsen said. “We’ve also made wonderful new friends – these people have become our extended family! Thank you to our friends and thank you to all who support the Ronald McDonald House. It is such an incredible place that makes a difference in the lives of so many families.”