|

Rita Van Fleet, who retired this year as The Nebraska Medical Center’s chief nursing officer, was one of the caregivers who was drawn by UNMC’s artist-in-residence, Mark Gilbert. This is among the many images that will be on display at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts as part of Gilbert’s “Here I Am and Nowhere Else: Portraits of Care” exhibit. |

The essays detail the experiences of patients, loved ones, health care workers and others who were exposed to the project.

A kickoff event for the exhibit will take place today from 7 to 9:30 p.m. in the Witherspoon Concert Hall at the Joslyn Art Museum.

The event will feature remarks from Gilbert, as well as Ted Kooser, former U.S. poet laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner who was treated for tongue cancer by UNMC’s William Lydiatt, M.D., in 1998.

Malorie Maddox, morning anchor for WOWT (Channel 6), will serve as emcee for the event, which is free and open to the public.

Gilbert, a Scottish artist, composed the works that make up the exhibit while serving as UNMC’s artist-in-residence for two years.

During his time at UNMC, he drew portraits of many different patients and their caregivers.

The patients, who included children and adults, were dealing with a variety of health promotion and illness situations from childbirth to medical conditions such as AIDS, head and neck cancer or some sort of organ transplant. Most of the collection will be on display at the Bemis Center through Feb. 21.

Today we feature an essay titled, “An Introduction to the Portraits of Care” by UNMC’s Virginia Aita, Ph.D., associate professor in the College of Public Health, and William Lydiatt, M.D., professor in the otolaryngology-head and neck surgery department, who along with artist Mark Gilbert, were part of a research team that observed the artist’s project.

“I have to be honest and say that I decided to participate in the project for my family. I also thought it would be a great way to educate others about HIV/AIDs. It is important to keep in mind that there is not yet a cure for the disease. After the artist started working on my picture I realized how enriched my life had become by participating in the project.” –Terri, A patient

“It is very easy to get caught up in the clinical and surgical aspects of care, and to gloss over the social and interpersonal aspects of it. The project was a thoughtful way of holding a mirror up to the situation. Not to mention, Mark was just a fantastic guy!” — Dan, A resident physician caregiver

The “Portraits of Care” project grew out of artist Mark Gilbert’s interest in the intersection of art and medicine and the interest of University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) faculty members Virginia Aita, Ph.D., and William Lydiatt, M.D., in care, caregiving and the arts. The three met when Dr. Aita and Dr. Lydiatt helped to bring Gilbert’s exhibition, Saving Faces to Omaha in 2006.

When Gilbert visited Omaha during the exhibition held at the art gallery at the University of Nebraska at Omaha (UNO), art department chairman David Helm asked Gilbert if he would consider returning in the fall of 2006 to become a visiting faculty member at UNO. Helm also conferred with Drs. Aita and Lydiatt about the possibility of Gilbert becoming an artist in residence at UNMC. When funding was secured for an artist’s residency, he agreed to return to Omaha to assume the joint position at UNO and UNMC. At that time, Gilbert and Drs. Aita and Lydiatt began to discuss prospective projects that would combine art and medicine. Two projects ultimately developed from this dialogue. The portraiture project was the primary research project in which Gilbert drew and painted portraits of patients and caregivers. The goal of the project was to study care and caregiving through portraiture. The second and separate project, “Teaching Observational Skills to Medical Students and Residents,” was developed to give Gilbert an opportunity to teach the subtle art of patient observation that can be critical in patient evaluation.

It was Gilbert’s keen observational skills that made both qualitative studies possible. This introductory essay will focus on the portraiture project.

Since ancient times, and in all parts of the world, artists have created images that represent health, illness and the art of healing and caregiving. There are also many images of disability. In addition, artists’ images have represented the inevitability of death, reflecting on its meaning.

Art history also is rich in images representing healers and caregivers. Images of healers such as the dual image of Asclepios, Greek god of medicine and his daughter, Hygeia, Greek goddess of health, Hippocrates and the American medicine man are just a few well known iconic healers. What these and so many other similar images, whether from ancient or more contemporary times, have in common is a keen interest in the interpretation of the physical and emotional manifestations of the human experience of health and illness and its larger meaning.

The artistic process is interpretive. In the visual art of portraiture, the artist observes the subject before him and through drawing and painting interprets what he sees. In the “Portraits of Care” exhibition, the drawn and painted portraits are not documentary in nature; they are interpretive. In the case of this project, Gilbert and Drs. Aita and Lydiatt were primarily interested in studying the portraits of patients and caregivers to see what they could learn about the subtle dimensions of care and caregiving through the artist’s observations, interpretive and artistic skills and secondarily, in analyzing the interpretations of the participants and gallery visitors.

Because the project was done as a research study, it was submitted and approved by the UNMC Institutional Review Board, an ethics panel with the primary goal to protect the people who participate in studies under its auspices. The patients and caregivers who participated in this project all agreed to participate and agreed to share their information included in this exhibition and catalogue. Many patients reported that they enjoyed the opportunity to “sit” for their portraits with Gilbert and to be part of the larger project of which this exhibition is the culmination. All project participants met with Gilbert for a “sitting” at least once, while selected participants met with him several times for additional sittings.

There are therefore, different drawings and paintings of several of the participants completed at different times. For patients who sat for Gilbert on more than one occasion, health status and the degree of perceived illness varied from time to time.

Patients and caregivers were recruited to “sit” for Gilbert through contacts with physicians, nurses and others associated with UNMC.

As Gilbert was drawing and painting the patients and caregivers, Drs. Aita and Lydiatt began to study the art works, the “research data,” to see what they revealed about care and caregiving. As mentioned above, the art works themselves are interpretive based upon Gilbert’s observations, so the analysis of the artwork was an interpretation of his interpretations (just as a physician’s history and physical examination are an interpretation of a patient’s interpretation of symptoms and history given in the examination room).

As the analysis process continued, Gilbert and Drs. Aita and Lydiatt gathered a multidisciplinary group together from the disciplines of art and medicine including Mark Masuoka, director of the Bemis Center For Contemporary Art; Aaron Holz, professor of art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Drs. Carl Greiner, Steven Wengel, and William Roccaforte, from the UNMC Department of Psychiatry; and several others who expanded the depth and scope of the analysis of art works. This group met several times to discuss the work and its meaning. In addition, as the patient and caregiver participants in the study became more vocal in their participation, they also added new insights to the analysis of data.

The analysis of the works uncovered three overall themes that concerned a) the patients and their health and illness experience, b) the caregivers and the personal, non-instrumental aspects of care, and c) the relationships between those who give and receive care. Each of these themes is discussed below.

A) The patients and their health and illness experience

Despite illness and other traumatic experiences associated with their health status, patient participants responded very positively to being drawn and painted. Their openness to Gilbert’s sensitivity towards them is evident in the intimacy and beauty of the portraits. Perhaps for patient participants this was a different and more welcome experience than the usual patient ordeal of being poked and prodded.

Overall, the visual representations depicted in the drawings and paintings show participants’ non-verbal facial and bodily expressivity. In viewing the portraits, one is first impressed by the artist’s ability to show the psychological and introspective qualities of patient participants.

These qualities imply the “interior” of participants’ experiences, the seriousness of illness and transitions in health status and the importance of care. For example, a participating patient named Marvin stated that the experience of illness had been a challenge, but had brought him into a relationship with God and healing. His portraits, done at different points in time, imply the transition he made through a life-threatening crisis, through stages of healing and back to health.

In the case of a portrait of another patient, Roger, one sees the enormous transition from health when he was an Air Force pilot, to illness and dependency caused by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Although his illness caused him to be extremely weak and vulnerable, his strength is visible in his gaze, his eyes still dance and he is able to respond and communicate through the computer technology attached to his chair. For medical patients like Roger, Sebron, and Megan, the waxing and waning nature of illness mixed with periods of improvement are evident in the portraits as well. Serial portraits of surgical patients, on the other hand, show their visually recognizable recovery in a relatively short period of time as seen in the portraits of Glenna and Anthony.

Another striking aspect of the patients’ portraits is that they show them to be “living” through their illnesses — patients show themselves to be remarkably “present” and functionally “healthier” than might be expected given their illnesses. In a few cases, the artist’s serial portraits of particular patients done at different points in time reveal the apparent link between the patient’s experience of illness or health and their sense of personal identity revealing probable transitions in identity as the meaning of illness changes over time. The complex interaction between the sense of personal identity and one’s psychological and functional health status is possibly some of the most difficult terrain that patients and caregivers must negotiate during periods of illness and in the caregiving relationship. Despite this, these portraits remind us by showing the patients as whole people not fragmented into neat catagories of sick and well, that wholeness whatever the circumstances remains throughout life, in all the transitions from birth, through adolescence and into middle and old age. Recognizing that psychological and functional health may often remain intact despite physical illness is important to acknowledge when illness strikes.

|

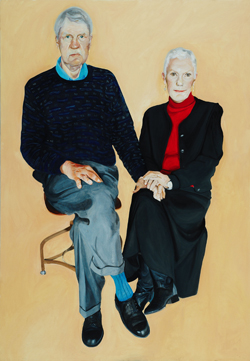

This image is of a couple named Robin, left, and Mardi, who are both cancer survivors who each cared for the other as they went through their respective illnesses. |

There have been several interesting dimensions of the analysis of caregiver portraits. One of those realizations became apparent as those organizing the research side of the project selected caregiver subjects. At first the research team assumed that for every patient subject, there would be a primary caregiver subject, but the fallacy of that idea soon became apparent. The question as to which caregivers should be chosen among the many that care for any given patient immediately arose. Should the caregiver be a family member? Should it be the physician or nurse? And, what about caregivers who may only be seen on occasion, the physical or occupational therapist, the hospital chaplain, and the social worker? Then there is the public health professional who is almost never seen, but who cares for whole populations of people including our patients — should this person be included? Likewise, there are caregivers who work in the laboratory or with other teams that perform the tests so critical for patients’ diagnoses and treatments. Finally, what roles do hospital administrators, not to mention members of the housekeeping staff play in the caregiving equation? Certainly any of these individuals in their caregiving capacities could qualify to be in a series of portraits of care. “Portraits of Care” depicts many different types of caregivers, those who are both seen and unseen in caregiving processes.

Another interesting dimension of the “Portraits of Care” project has been that portraiture, by its nature, stops the action of the subject. Caregivers in their usual roles are active people, always doing something to care for the other. In speaking with some of the caregivers whose portraits are part of this project, the research team learned that they felt somewhat awkward just sitting for the portraits because they weren’t “doing” anything. They were also not used to being the subject of an artist’s gaze. They are not usually the ones to be examined in their day-to-day lives. In this project the artist observed caregivers as well as patients. In this sense, the caregivers became “vulnerable” in the same way that the patients are vulnerable to being observed again and again during physical examinations during the processes of caregiving, only in this case, it was as the artist looked at and drew them. In both cases, whether patient or caregiver, the subjects of these portraits appear thoughtful and emotionally engaged, if sometimes a bit vulnerable.

C)The relationship between those who give and receive care

In the whole group of the “Portraits of Care,” only one picture depicts both patient and caregiver together. It is the picture of a married couple, Mardi and Rob, both cancer survivors, both caregivers for the other. Their portrait pulls the viewer into the intimacy of their symbiotic relationship. When the couple saw their portrait, each remarked that it helped them see “aspects of each of us which we had previously not recognized,” among these the vulnerability that can come with a diagnosis and treatment of cancer. … Mardi also uncovered another twist in caregiving when she mentioned that in her normal life she was working in a genetics laboratory on a research project having implications for cancer therapy. Working for the “greater good” of the population, she never thought she might benefit from the research in which she was engaged. Although a patient herself and a direct caregiver of Rob, she was also in a very real sense, one of the unseen caregivers of a population of people who might someday benefit from her research.

In making sense out of the many findings arising from the analysis of the portraiture project, we recognized that care entails a ritual of relationship of those who are involved in its exchange, a mutual experience shared by those who give and who receive care. The ritual has a sense of ceremony characterized by the seeking of care (by a patient) and the reciprocal interpretive assessment of need for care and subsequent intervention, the “laying on of hands” (by the caregiver). The ritual by itself holds potential meaning and therapeutic value.

Perhaps the most important accomplishment of the project was that it helped better establish the meaning of care and caregiving. Victor Frankl in his work, “Man’s Search for Meaning,” wrote that the most important drive in life is to find meaning. Care and caregiving sit at the intersection of two of life’s most critical experiences, transitions in health and illness and in the work of caring for others. … The idea often expressed by subjects of “giving back” or helping others to learn about care attests to the drive to find and assign meaning in one’s experience.

The primary implications of this project are beginning to unfold, but the secondary objective will not be realized until the exhibition is seen, experienced and discussed by both public and professional audiences. The research team, therefore, invites and encourages public discourse and feedback about this exhibition and the special events that highlight certain aspects of it. Care and caregiving are an ongoing part of everyday life; they are not simply technical tasks performed by nameless people in institutional settings.

We thank the patients and caregivers who participated in the “Portraits of Care Project” for allowing us to learn more about care and caregiving through their participation.