In a major innovation in organ transplantation that could offer hope to millions of Americans with organ failure or diabetes, a study by Ximerex, Inc. in conjunction with researchers from UNMC has demonstrated that acute rejection of pig heart transplants could be prevented without the need for severe immune suppression. The findings were reported in the February issue of the Annals of Surgery.

|

Dr. Beschorner |

“Our findings represent a key step towards ultimately being able to use pig organs in humans with organ failure or diabetes,” said William E. Beschorner, M.D., founder and president of Ximerex (KI-MER’-ex), Inc. and an adjunct professor of surgery at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. “In addition to heart transplants, the technology developed in this study would also be applicable to kidney, liver and pancreatic islet cell transplants.”

About the study

In the study, 13 experimental sheep received heart grafts from pigs containing sheep cells. Only one developed acute vascular rejection typical of pig xenograft rejection. Five developed a milder form of rejection, cellular rejection, which responded to steroid therapy. Cellular rejection is typically seen following a human-to-human organ transplant. The remaining seven sheep, followed for up to 70 days, never developed significant rejection. The recipient sheep experienced minimal complications and retained their ability to fight infections.

In contrast, all 12 of the control sheep, transplanted with heart grafts from pigs not containing sheep cells, rejected their grafts by acute vascular rejection in four to eight days, even though they received the same immune suppression.

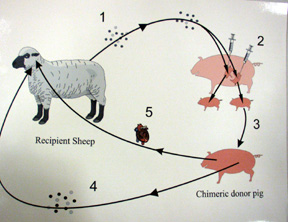

The key to this breakthrough was the transfusion of bone marrow cells from the recipient sheep into the donor pigs during fetal development.

The key to this breakthrough was the transfusion of bone marrow cells from the recipient sheep into the donor pigs during fetal development.

After the pigs were born, white cells from the pig’s spleen, containing both sheep and pig cells were transfused into the recipient sheep, followed by the heart transplant. Modest immune suppression was given, less than that given for a human receiving a human heart transplant.

Dr. Beschorner, senior author of the study, said growing the patient’s cells within the donor pig accomplishes the major goals of transplantation within the donor pig, before performing the transplant.

Next step: studies in non-human primates

“The fetal pig environment is ideal for the growth of cells from another species. It also is ideal for the development of immune tolerance and tissue accommodation,” he said. “The patient’s cells learn to ignore the pig tissues. The donor pig tissues become adapted to resist injury by antibodies against pig tissues. The dilemma in xenotransplantation has been that pig organs are very different from human organs, triggering severe rejection reactions. How do you block these reactions and leave the patient’s immune system intact? Our method of transplanting the donor pig gets us past this roadblock.

“Before our new technology can be tested in human recipients, we need to do the appropriate studies in non-human primates. Those could prove more challenging than our study in sheep. However, we have successfully grown human cells in fetal pigs, so we are optimistic about the non-human primate transplant studies.”

Dr. Beschorner said the primate studies would take one to two years. Funds to support these trials must first be obtained.

Curbing the shortage of donor organs

Each year 750,000 Americans die of heart failure. The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation estimates that 50,000 lives could be saved with heart transplants. However, due to the shortage of donor organs, only about 2,200 transplants are performed.

It is estimated that if xenotransplantation were as effective as human organ transplantation, 500,000 Americans could be helped each year. In the developed world, as many as 1.3 million patients could be helped annually. The average reimbursement rate for procuring a human organ is about $25,000. At this rate, the potential market would be about $32 billion.

About Dr. Beschorner

Dr. Beschorner is an experimental pathologist and has been studying the problems associated with organ transplantation for more than 25 years. His early studies in this field were done at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Md. He relocated to Nebraska in 1997.

For more information, visit http://www.ximerex.com, or e-mail

beschorner@ximerex.com.