|

From left, Nancy Andrews, case manager-oncology, Dr. Peter Coccia, Lora Webster, Brent Rasmussen and Dr. James Neff. Photo by Walter Brooks. |

In fact, Dr. Neff and Peter Coccia, M.D., professor, department of pediatrics hematology-oncology, share a total of three patients who competed at the Paralympics Games – Webster of Cave Creek, Ariz.; her teammate Allison Aldrich of Schuyler, Neb.; and Brent Rasmussen of Omaha.

Rasmussen’s men’s volleyball team did not make the medal round, but he was one of the assistant coaches on the women’s team and had personally trained with Aldrich on numerous occasions.

The three athletes share the same body alteration – they have had one of their legs amputated by Dr. Neff. Webster and Aldrich required amputation due to osteosarcoma (bone cancer) and Rasmussen lost his following a traumatic injury.

“I’d never held a real Olympic medal – that was a privilege,” Dr. Neff said. “But even more so, I am honored to be a part of these outstanding athletes’ lives. Yes, I performed the surgeries on all of them and Dr. Coccia guided the women through their chemotherapy. All of us – clinical staff and prosthetic specialists – did our job, but the athletes are the real story here.

|

Lora Webster and Dr. Neff. |

Aldrich lost her right leg when she was 7-years-old. Now 16, she said she never experienced any sense of being different for having a prosthetic leg.

“When you grow up in a small town, your grade school friends are with you all the way through high school,” Aldrich said. “All my friends grew up with my leg, we did everything together, and I never felt different in any way.”

Webster, on the other, lost her leg when she was 12. When she entered high school, she said it took a while to make new friends. But, her best memory is when she received her first prosthesis. After having her leg removed in March 1998, it took almost seven months of post-operative healing and therapy before she could be fit with a new leg.

“I felt I was ready for a new leg a week after surgery, but obviously Dr. Neff knew better,” Webster said. “I pestered, begged and did cartwheels every time I came to the clinic trying to convince him to give me my leg. Two-legged people can’t possibly know how much they take their legs for granted. When I finally got my new leg, I was so happy; it actually felt like a miracle.”

In 2002, Rasmussen was being a Good Samaritan and assisting a stranded motorist when another vehicle crashed into the disabled car, crushing both his legs between the two vehicles and necessitating the eventual removal of one leg.

|

Brent Rasmussen returns the ball as teammates Essam Hamido, top left, Chris Seilkop and Joey Evans watch. Photo courtesy of Yahoo.com. |

|

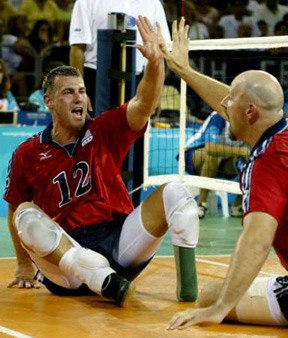

Brent Rasmussen, left, shares a high five with teammate Rob Osbahr. Photo courtesy of Yahoo.com. |

“Getting a new leg is never a quick process – each prosthetic leg is different, has different fittings and sockets and feet attached,” Rasmussen said. “I’ve had three different legs so far. I still cannot walk great distances without having to stop and rest. Sometimes my leg might swell up and the prosthesis won’t fit properly. It’s one of the reasons why I have such respect for Allison and Lora. They have been through all of this at much younger ages and for a lot longer time and they are two of the best athletes I’ve ever met.”

All three athletes came to the Paralympics through different paths. Rasmussen’s story was written up in the Omaha World-Herald, and he was recruited to play for a local softball team. He soon joined the Nebraska Barons in the U.S. National Wheel Chair Softball League – where he set single season records for home runs and runs batted in.

At the national tournament in 2003, the Barons went undefeated and took the championship. Paralympics scouts at the tournament asked Rasmussen to join the Paralympics sitting volleyball team.

Aldrich also was written about in the Omaha World-Herald and when Rasmussen read about her, he encouraged her to pursue the women’s team. She had developed into one of Schuyler’s best athletes, and played basketball, soccer, golf and volleyball.

Webster already had a reputation as an outstanding athlete in the Phoenix area – Cave Creek is a suburb of Phoenix. She was recruited to try out for the Paralympics team by a recruiter she met during a tournament in California. Webster met Aldrich later that year when they both went to Atlanta for team training.

In Greece, Paralympic athletes used the same facilities as the Summer Olympic Games, including holding opening and closing ceremonies in Olympic Stadium. For Rasmussen, Aldrich and Webster, it was the thrill of a lifetime, a real wake-up on global athletic competition and a reminder of how fortunate they are to be Americans.

The sitting volleyball competition requires all players to sit on their rear ends and use only their hands for mobility. The net is much lower and the game actually faster than traditional volleyball. Athletes have to maneuver their bodies and still make contact with the ball. It requires a lot of training to get the rhythm and patterns, and each athlete has to literally – with a lot of bruises and soreness – develop “buns of steel.” Sitting volleyball is a tough sport where legs are no advantage.

|

Allison Aldrich in her Paralympics warm-up suit. |

“We also realized how many athletes come from countries where the social attitude toward people with physical impairments is still pretty backward. We noticed athletes who would never take their legs off in public – they’d hide or go to the bathroom. They were ashamed of having a missing limb because they were from cultures that shunned them. The whole experience in Greece reinforced our appreciation for living in a land of much greater opportunity and acceptance of people with physical impairments.”

But the Paralympics also introduced the three athletes to another aspect of America that they are dedicated to changing. Most Americans have no real awareness of the Paralympics. In fact, over and over, the three encountered people who thought the Paralympics and Special Olympics were the same thing.

“It’s really frustrating,” Webster said. “We were on the airplane crossing the Atlantic and the attendants proudly announced over the loudspeaker that the United States Special Olympics volleyball team was on board. It happens all the time. We compete with the same guidelines as the Olympic Games. We compete for gold, silver and bronze medals. You win or you go home. In the Special Olympics, the athletes have developmental disabilities and everyone receives a medal and a hug at the end of their competition.”

The trio is determined to get more press and public awareness for the Paralympics before the next games in China in 2008.

On Oct. 25, the Paralympics team joined the Summer Olympics team for the official reception and photograph with President George W. Bush at the White House.

“We didn’t get to shake the president’s hand because there were so many athletes and we were towards the back of the crowd and he didn’t stay long enough for us to get up close,” Rasmussen said. “But it was really cool that we got to meet so many members of the Summer Olympics team. They all truly respected us as fellow athletes.”

“And all of us Olympians seem to share one goal,” Aldrich said. “We all want to get to China in 2008 and do it again. In fact, Lora and I really believe our women’s team can take the gold next time.”