|

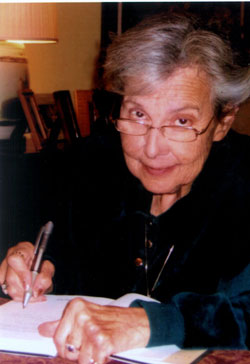

Lilian Furst, Ph.D., will deliver the first Wilson lecture on Thursday, Oct. 4 at noon in the Eppley Science Hall Amphitheater. Dr. Furst will show how 19th century literature painted vivid pictures of medical advances of the time. |

Lilian Furst, Ph.D., Marcel Bataillon Professor of Comparative Literature, Emerita, at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said one can get a vivid picture of the impact of these advances by reading the century’s literature.

Dr. Furst will paint just such a picture when she presents the first Wilson lecture on Thursday, Oct. 4 at noon in the Eppley Science Hall Amphitheater.

“The 19th century was a very dramatic time in terms of medical advancement,” Dr. Furst said. “Because of this, the world changed drastically over this period.”

During her lecture, Dr. Furst will use several 19th century works, including Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novel, “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” and Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1893 short story, “The Doctors of Hoyland,” to illustrate the reality of such advances.

The 19th century saw the introduction of several new medicines and the story of Jekyll and Hyde — in which the respectable Dr. Jekyll takes medicine that turns him into the menacing Mr. Hyde — shows how these new drugs were met with fear by many, Dr. Furst said.

“In the end, Dr. Jekyll takes his medication, turns into Mr. Hyde and is not able to revert back to being Dr. Jekyll,” Dr. Furst said. “People were afraid the new medicine would change them in irreversible ways.”

“The Doctors of Hoyland,” in which a male doctor struggles to deal with reality after meeting a female doctor whose skill proves superior to his own, illustrates the rise of women in the world of medicine in the 19th century.

Learning through literature can be incredibly valuable for physicians, Dr. Furst said, because it can put a human face on the impact of medical developments.

And physcians who continuously remember that their patients are humans and not specimens, stand to be much more effective, said Dr. Furst, who was the daughter of two Austrian dentists who fled the country after the Nazi’s invaded.

“If physicians can get their patients to like them and trust them, they can do a much better job of treating them,” Dr. Furst said.

Dr. Furst said her father went on to work at Stanford University after migrating to the United States. Even in the progressive environment at Stanford, Dr. Furst said he found some physicians who took on a cold attitude toward patients, choosing to view them as subjects rather than humans.

While technological advances have resulted in better and longer lives for many, Dr. Furst said, literature and other humanities remind physicians that they are indeed dealing with people.

The Wilson lecture is sponsored by the Charles Wilson, Humanities in Medicine (HIM) Program. Charles Wilson, M.D., initiated the HIM Program at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln 11 years ago to encourage students interested in studying medicine to major in the humanities during their undergraduate years. He expanded the program to UNMC three years ago to sponsor humanities lectures and other related activities in the medical center.

Dr. Wilson is a former UNMC clinical professor who recently announced he would step down from the University of Nebraska Board of Regents after serving for 18 years as the District 1 representative.

He has been a longtime proponent of having aspiring health care professionals learn humanities — his own story serving as an example. Dr. Wilson dropped his pre-med major to study art, literature, music and other humanities — much to the chagrin of his undergraduate counselor who said, “Mark my words, young man. You will never get into medical school.”

Dr. Wilson received his M.D. from Northwestern University in 1964.

“I have never regretted doing that (quitting the official pre-med program),” he said during a lecture at UNMC in 2005. “You can major in history or literature or art and still go to medical school. My colleagues often tell me ‘if I had to do it over again I’d take more — you fill in the blank.'”