When UNMC doctoral candidate LeDon Bean graduated from high school in 1986, he already had a vision of what he wanted to do with his life — study medicine.

When UNMC doctoral candidate LeDon Bean graduated from high school in 1986, he already had a vision of what he wanted to do with his life — study medicine.

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Calif., Bean’s parents often bought him chemistry and erecter sets. He developed a love for math and science subjects. His grandparents, a Baptist pastor whose wife was the church’s queen mother and leading missionary, often took Bean with them to visit sick and aging members at their homes, while hospitalized or confined to nursing homes. He grew up wanting to help others.

Then his father died.

“My father died shortly after high school graduation,” Bean said. “Instead of college, I ended up going to work to help support my mother and sister. I was employed in the banking industry for a few years. As it turned out, it was a bittersweet relationship. I learned a lot about banking, economics and finance. However, over and over, I trained new employees just to watch them be promoted over me. And it was always for the same reason — they had a college degree and I didn’t.

Pursuing a degree

“After experiencing this negative-positive or positive-negative reinforcement, I got the message. I entered the University of Southern California (USC) in 1989 and graduated with a bachelor’s of science degree in chemistry in 1994. I was the only African American in my class to get a degree in chemistry. There had been no other blacks with a major in chemistry ahead of me or behind me during my four years at USC.”

|

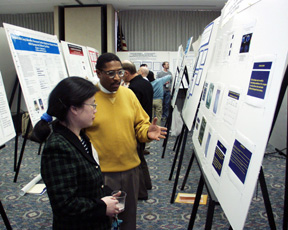

LeDon Bean and Xinying Li, M.D., Ph.D., a UNMC post doctoral research associate, review his poster at UNMC’s Six Annual Cardiovascular Research Symposium. |

Being one of the few blacks majoring in hard science didn’t surprise Bean. His primary and secondary education had been in public schools with predominately black students and his school environment was not pro-active in encouraging young people towards mathematics and science. Bean and a handful of like-minded students really had no mentors and had to be self-motivators. In fact, Bean’s family members were progressively pressuring him to consider the ministry and walk in his grandfather’s ministerial footsteps.

After USC, Bean moved to Omaha to attend Creighton University. At the time, Creighton had a promising program aimed at developing minorities for medical school. But Creighton abandoned that program and Bean decided to transfer to UNO. He pursued a master’s degree in biological sciences with an emphasis in physiology. The preponderance of his courses for his master’s degree was at UNMC. This facilitated Bean’s transition to his doctorate studies in neuroscience pharmacology.

Inside the world of research, medicine

“I wish to study the nature of protein interactions in such neurodegenerative diseases as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis,” Bean said. “I am maintaining a foot in both camps of research and medicine. However, I’ll wait until I am closer to obtaining my doctorate and then assess my situation in terms of the research and grant opportunities, my strength as an independent researcher, my publication record and the available tenure-track possibilities before reevaluating a medical education.”

Earlier this year, at UNMC’s Sixth Annual Cardiovascular Research Symposium, the largest annual gathering of cardiovascular research presentations on campus, Bean was the only African American among 33 presenters.

Helping minority youths

The outstanding opportunities Bean has received at UNMC inspired him to organize his first minority youth education workshop in 1999. He petitioned the Office of Student Equity and Multicultural Affairs to sponsor a day on campus for 36 students from Omaha North and Central High Schools and Monroe Middle School. All the students were picked from the Omaha Public Schools’s Minority Scholars Program and continue to be so each year.

“I can’t remember the time when I haven’t been a mentor,” Bean said. “I’ve always had some relationship with the community, with high school students, going to the movies with them, having dinner with them, sitting and talking about their school work, and helping them to strategize about their futures and how to achieve their goals.

“In 1999, it was a logical step to seek UNMC’s assistance in trying to reach more youths in our community and to take advantage of the many health science professionals and administrators on this campus who are willing to communicate with our students. I was born and raised in the shadow of USC. My friends and I played football on the USC campus, attended movies sponsored by the USC film school and I read and studied in the campus libraries. I always had a familiarity with a college environment.

“But to many minority kids in Omaha, UNMC may as well be on the moon. My efforts, and those of all the people who support our annual youth workshops, are to build a physical connection between minority students and the university, to acquaint our youth with campus activities and opportunities, and, most important of all, to demonstrate to them that there are individuals of the community and on campus who are interested in them, in their well-being and in their educational future.”

“I’m not only grateful for the opportunities UNMC has provided for me, but I am especially thankful that so many departments, faculty and students are willing to assist in exhibiting viable alternatives to the negative cultural interests that bombard our youth daily. Every act of concern, every minority faculty member, student or administrator they meet on campus, is another affirming incentive for our youth to believe that they can achieve their goals, as well.”