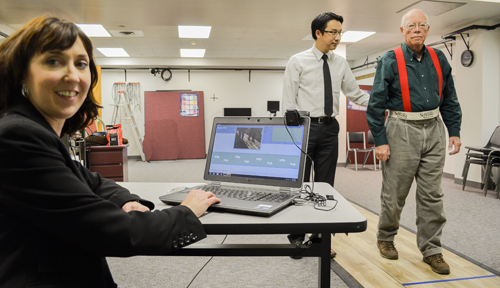

There is the old joke about not being able to walk and chew gum at the same time. But there’s something to it, scientifically, said Dawn Venema, Ph.D., assistant professor of physical therapy education. As a clinician, she saw it all the time.

Now she studies it.

When she was a physical therapist in the field, she worked with geriatric clientele, and with some, she noticed, “People literally couldn’t walk and talk at the same time.”

|

Joseph Siu, Ph.D., and Dawn Venema, Ph.D. |

When Dr. Venema joined the faculty at UNMC, it seemed like a natural line of research.

She collaborated with Joseph Siu, Ph.D., who was then at the College of Public Health and now her next-door neighbor in PT. He’s also studied dual-task costs — how it affects us when we try to do two things at once.

Like texting and driving?

“It’s the same thing,” Dr. Venema said. “As much as we like to think we can multi-task, the quality of the task suffers as we try to do more than one thing at a time.”

But even more so among older adults who have dementia: “Their dual-task cost is really great because they don’t have as much cognitive resources to draw on,” Dr. Venema said.

Drs. Venema and Siu did a study, published in the Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. They found that older adults doing a walking test were slowed when asked to simultaneously complete a cognitive (counting/math) task. The results were more dramatic among patients who started off with lower cognitive scores.

See sidebar for more information on the study.

But interestingly, all were able to at least attempt it. No one completely shut down, mentally or physically.

“Perhaps we can challenge people with dementia more than we think,” Dr. Venema said.

And that led to a second, pilot study, PT/cognitive training among a small group with dementia: those given “easy” cognitive tasks improved on about half of their outcomes; but those in the “hard” cognitive-task group improved on all outcomes, and by greater margins.

So maybe there’s hope.

They aim to expand to a full study, but they need more enrollees with dementia, whose families would need to give permission. Those spots are understandably tougher to fill.

For information about the study, call 402-559-6594. For further information on clinical trials please call the Research Subject Advocate Office at 402-559-6941.